The use of propaganda is ancient, but never before has there been the technology to so effectively disseminate it.

Introduction

The story of disinformation, fake news, post-truth, a phenomenon defined in the past with words such as propaganda, gossip, urban legend or myth – all referring to information that has been manipulated – is brimming with spectacular examples. However, the development of new technologies changed the context in which these phenomena take place. It is easy to drown in the flood of not necessarily verified or trustworthy information. At the same time, the Internet allows for a much easier access to knowledge, a fundamental asset in confirming what we have read or seen.

False and manipulated information does not spread by itself – it is disseminated by people. You can help stop fake news by checking its credibility before eventually passing it on or debunking a misleading story in case it was already circulated by other sources. Conversely, you can also contribute to increasing its range. Counteracting disinformation should now be considered an important element of journalistic ethos and a standard practice for watchdog media. We created our Dealing with Disinformation. A Handbook for Journalists to facilitate this important task.

The critical journalist’s eye is an indispensable tool, but by far not the only one. The Internet contains a great number of resources – many of them free – that allow you to check whether other media outlets already covered the topic, where on the Web did the photo appear before or what experts have to say on the subject. At your disposal are also more advanced solutions employed in professional investigative journalism, allowing you to check exactly where and when the material was first published and whether it was tampered with. Chapter I of this manual covers a number of helpful fact-checking tools.

Every medium can – and should – work to counteract the spread of disinformation. You can achieve this goal by skillfully debunking false information or simply by creating quality content your recipients can trust. The mechanisms of effectively reaching out with a corrected information and establishing long-term credibility are described in Chapter II.

And what if your efforts to debunk fake news make you a target for revenge? You can never rule out this scenario, but you can prepare yourself for when it happens. Chapter III will teach you how to protect yourself against online assaults and how to respond once you are attacked.

We wish you good (and informative) reading!

Chapter I. True or False? How to Spot a Fake

1. Disinformation — Ancient Phenomenon in Modern Reality

In recent years, the age-old mechanisms of propaganda, populism and manipulating information have significantly widened their scope due to social, economical and technological changes. We are now able to create progressively more convincing montages of photos, films and statements. The ad-based business model of news portals requires them to publish all information as soon as possible, restricting the time available for critical analysis and allowing for further spreading of unverified news. Our attention (and clicks) are increasingly drawn by sensationalized, manipulated headlines (called ‘clickbaits’), which in turn direct us to tenuous content.

The surfeit of information is a factor in increasing the popularity of social media portals, processing the surrounding informational chaos into a set of information tailored to a specific user. That leads to appearance of filter bubbles, where each of us receives a customized sliver of reality adjusted to our preconceptions. Social media facilitate viral spreading of unsubstantiated information. Publishing such content requires hardly any effort, while the recipients often indiscriminately trust the information shared by their friends.

The Filter Bubble Trap

Imagine your newspaper appearing daily right on your doorstep. However, it is not the same newspaper anyone else gets. This one was printed specially for you and contains only the information deemed relevant to you by the publisher – and just as many ads tailored to your needs and financial means.

Enter Facebook, employing an algorithm that suggests content based on information gathered about the platform’s users. The goal is to make this personalized information as relevant and interesting as possible, which really means generating likes, comments, clicks and profits. This selection is based not only on sex, age or location, but also on character traits, political views, sexual orientation or health inferred from both our consciously published information and the digital trail left by every single one of our online actions.

Google search engine will also display different content for each user. What appears in our search results is based, among other things, on our browsing history.

This adjustment of displayed content causes the users to receive information confirming what they already believed in the first place. Despite having access to global news sites featuring content from all around the world, they never actually stick their heads out from their bubble. Convenient as it may be for an ordinary user, for journalists it could be a dangerous trap.

We are yet to invent a tool that would faultlessly separate true information from false. That is why it is indispensable to cultivate a keen and sceptical journalistic eye. The Internet can be your ally in this endeavor.

This chapter features specific examples of what should arouse your suspicion and presents currently available tools for confirming or dispelling your doubts about the credibility of received information or its source.

2. Verifying Information Found Online

The importance of scepticism in journalism cannot be overstated, and verifying sources lies at the very base of the profession. However, given the overabundance of information surging at us from all sides, one exceptionally valuable skill is being able to quickly separate possible facts from the news likely to turn out false or manipulated.

Bombshell Alert

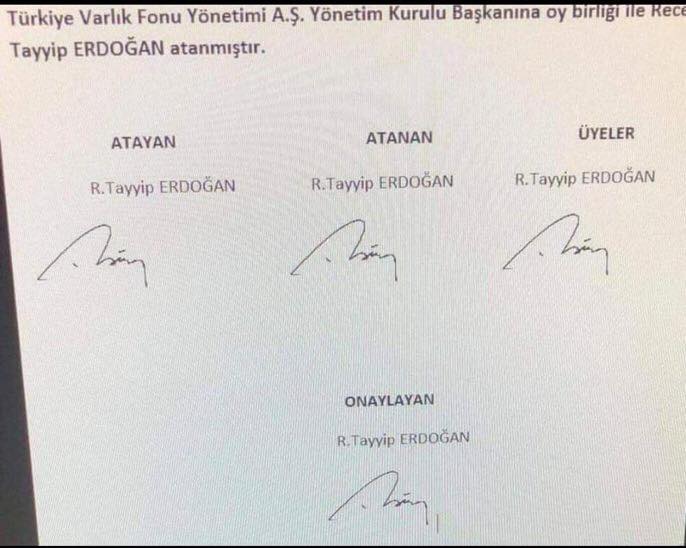

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan appointed himself as the head of a 200-billion-dollar fund – this (fake) news also appeared on Polish news sites. Such widespread popularity owes not only to the protagonist and controversies surrounding his politics, but also to the attached graphic appealing to readers’ imagination. Marcin Napiórkowski from Mitologia Współczesna (Modern Mythology) portal, an expert in dismantling fake information into basic elements, decided to take a closer look and exposed it for a fake that it is.

It seems that originally the image containing four signatures of the Turkish president (copied and pasted from Wikipedia) surfaced as a satirical way to accurately comment on his current actions. Next it was shared through American social media (link, link) and 24 hours later reached Poland.

The news appeared on Polskieradio24.pl and Donald.pl portals. (…)

How do we know it’s a fake? It is impossible to find a confirmed source of this amusing graphic; the font doesn’t match the one used in official Turkish government documents and there is a typo in the presented fragment – states Napiórkowski.

Source: Mitologia Współczesna

Where to start? Here are some characteristics often shared by manipulated information:

- flashy headline and shocking lead, promising a non-existent sensation, aiming to attract clicks, which in turn translate to profits from the ads featured on the website;

- emotive language and photos, calculated to stir up emotions, predominantly negative ones;

- no source for published information, citing a completely unknown source or one that is widely recognized as a fake news factory;

- errors in language, orthography and many calques;

- no specified author, no information about the author and editorial staff.

On Everyone’s Lips: The Blue Whale Challenge

In 2017, the Polish Minister of Education obliged school headmasters to warn parents about the dangers posed to minors by computer games. The Blue Whale Challenge, allegedly the cause of over 100 suicides in Russia, alarmed the global media. Marcin Napiórkowski analyzed the events leading to this widespread media panic.

It all started with Galina Mursaliyeva’s article on ‘Novaya Gazeta’ website published on May 16th the previous year. The author described the (real) investigation into the death of two teenage girls and linked it (without sufficient proof) to the deaths of 130 children.

The article turned out to generate a lot of clicks and was therefore reprinted by other media outlets, sometimes embellished with new details, sometimes paraphrased just enough to avoid being sued for plagiarism.

On February 16th 2017, ‘Novaya Gazeta’ published another article by the same author, which presented the challenge as a global phenomenon and Russian cybersecurity task force intervention as imminent.

And so, the article attracts even more clicks. The media around the world are talking about it. Soon it reaches Poland. [...]

When I compared several publications featured on Radio Zet news site, Wyborcza.pl and Mamadu.pl, it became apparent that all of them were compiled from the reports by ‘Novaya Gazeta’. It is also evident that some of the authors simply copied from each other, not even consulting the Russian sources! – he says.

The manipulated story of the Blue Whale Challenge that shocked all Poland was propagated by a few portals borrowing ‘facts’ from each other. To avoid making the same mistakes, always remember the following rules:

- Consult the sources. Check from where the information originated and who else writes about it.

- Scrutinize cited sources and experts. Does the material have the most up-to-date sources? Do you recognize the expert behind a quote? What do you know about their achievements and competencies?

- Check for contradictions in the text.

- Verify the facts, paying special attention to errors in numbers, dates, time, first and last names of the people included, appropriate attribution of their titles and functions and precision in quoting statements.

- Go directly to the source. Ask for a comment, go over as many details as possible and clear eventual doubts.

- Find additional sources. A single publication is not a valid source of information. As a journalist, be sure to always use at least two sources.

- Cross-reference presented data with statistics available in official public sources, e.g. the country’s public statistic authority, police reports or Eurostat.

The following internet tools may prove to be especially useful when trying to verify unconfirmed information:

- RSS feeds/content aggregators (Rich Site Summary) also known as: RSS Reader, News Readers, News Aggregators, enable you to harvest content from your choice of information portals, blogs, Twitter accounts and more. RSS does not only keep you up to date, but also allows you to check the presence of information in other channels. You may want to try out open source RSSOwl available for Windows, OS X and Linux. Another popular choice is Google News, although in this case the provider chooses which websites to include in your feed.

- Advanced search engine options allow you to look up an entire phrase, files with particular formats or information published at a specified time. Other options include e.g. tracking a document on public institutions’ websites lacking adequate retrieval mechanisms. These tools are featured in open search engines such as StartPage or DuckDuckGo, as well as in Google Search. The following functions may turn out to be especially useful:

- “” look up full phrases (e.g. “US President”);

- site: search inside one website (e.g. president site:theguardian.com);

- - exclude from search results (e.g. US president -Trump);

- filetype: find files with a specific format (e.g. US president filetype:mp3).

- When verifying information, always remember to step outside your filter bubble (cf. The Filter Bubble Trap). Configuring your browser to block all tracking and switching to search engines with no personalized results (such as StartPage or DuckDuckGo) can go a long way toward escaping your personal bias.

- Specialized scientific research search engines such as Academia.edu, ResearchGate, SSRN or Google Scholar are useful in verifying the credentials of a supposed expert quoted in a publication you are trying to authenticate or just finding scientific papers concerning a given subject.

3. Verifying the Credibility of Internet Sources

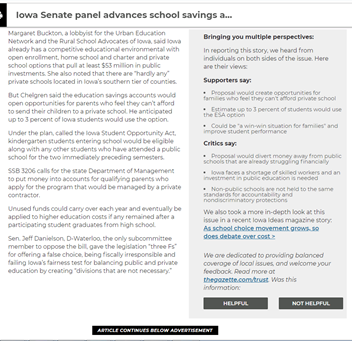

You can expedite the preliminary assessment of the published information’s credibility by scrutinizing the Internet source from which it originated. This is especially helpful in the case of portals you do not know and will enable you to pinpoint the sites specializing in spreading false or manipulated content. Although their news – whether political or cultural – may have some basis in reality, they are designed solely for the purpose of baiting unaware readers to click the thrilling headline and adding another hit to the counter. Nevertheless, many people consider them to be a credible source of information.

Be especially cautious about the content published on a given website if:

- it is dominated by clickbaits;

- it displays a lot of trashy ads (such as ‘Learn a language in one week’, ‘Lose 20 lbs with this secret technique’ etc.);

- URL address looks suspicious (e.g. wwwnytimes.com – notice the lack of a dot after ‘www’);

- there is no information about the author on the website;

- the Whois registry (whois.domaintools.com) entries about the site are incomplete;

- the domain is registered in a different country than the target of its publications or the administrator seems untrustworthy.

There are some cases in which the actual owners of a domain opt to remain anonymous and contract the services of intermediaries. You can still try to gather other information about the domain, e.g. what other websites are hosted on the server hosting the site you are trying to verify. To that end, use:

- Reverse Whois Lookup, a process designed to check other sites hosted on the server containing the domain you are looking into. Free tools that allow you to do this include ViewDNSInfo and DomainEye.

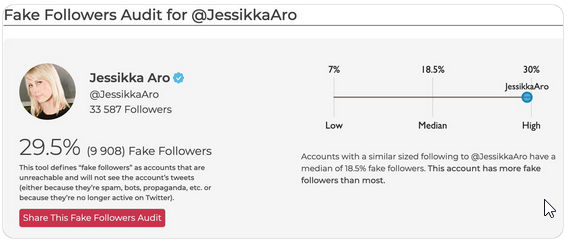

Social media created perfect conditions for incubating false information. A lot of fakes come from fake accounts administered through bots or people pretending to be someone else. Identifying a fake account is an important step towards successful verification of given information.

Is This Account Real?

In April 2019 in Poland teachers went on general strike – first time in country’s modern history. Oko.press investigative portal investigated the seemingly grassroots movement of people criticizing the strike. Dominika Sitnicka exposed the most active accounts as fake, stressing that their previous posts do not reflect authentic interest in what is happening, suggesting it to be a commissioned communication (by the ruling party’s politicians). She verified one of the accounts through reverse-searching its profile picture (see below): The photo of Mrs. Ula (criticizing the teachers strike) can also be found on the stock photo services pirating images from Instagram posts.

When verifying a profile, it is crucial to maintain a vigilant investigator’s eye, monitoring the following elements:

- URL address and account name. The URL address not matching the account name or containing random numbers and characters may indicate that you are dealing with a fake account. To verify the government institutions’ accounts, go to their official websites (domain usually includes ‘gov’ and the country code) and check whether they have a social media account.

- Profile picture. Fake accounts often make use of stock photos, some of them reused over and over again for different accounts. TinEye.com browser allows you to check whether the photograph appeared before in a different context. Increasingly often, fake accounts mislead us with images of people who do not exist; these images are generated automatically and often feature blurred backgrounds, asymmetrical facial features or hair ‘growing into’ the face.

- Account activity. Be careful about the accounts that post unusually often or regularly publish materials at the same time of day.

- Published content. Fake accounts usually do not post a lot of original content and mostly reprint what other people have published. If you suspect that the only purpose of the account is to deliver clickbaits on redundant topics, enclose the phrases from the text in quotation marks (“”) – you might find more suspicious accounts sharing the same story. Be cautious when you stumble upon a description unrelated to published content (e.g. the name suggests an account dedicated to a movie, while in fact it serves a political party’s agenda), hashtags not matching the information or automatic responses from other accounts. Analyze the conversations between the user and his followers – do they appear convincing, or were they just copy-pastes provided with external links?

- Location marker. Check whether the marker matches the published content.

- Who’s watching? Bot accounts usually do not exist longer than several months, do not have many followers, but are observing many users. One of the indicators of bot activity is a sudden surge of observing and observed accounts. You can check the history of this dynamics with Wayback Machine. The nonsensical comments under a post or suspicious followers’ accounts may also be a clue that we are dealing with a fraud.

Screenshot by Beata Biel

Journalists’ inboxes are flooded daily with emails of varying credibility. Many of them are drafted by PR professionals as information virtually ready for publishing. A journalist’s job is to establish whether this information in not solely a PR material. Check whether:

- the same content was published before on the Internet? (search for it enclosed in quotation marks)

- it is not a direct (machine) translation from another language?

- Is the sender’s e-mail address listed online?

The Festival That Never Was

In 2017, the internet exploded with the news of the luxurious new Fyre Festival in the Bahamas. The tickets for this ‘once in a lifetime experience’, ranging in price from $500 to $12,000, were sold out almost immediately. The organizers employed popular Instagram models to promote the event. On the eve of the festival it became clear that there are no stars, no stages and no extravagant villas – the whole thing turned out to be a giant flop. Only then the media, who up to this moment indiscriminately repeated the contents of received publicity materials, began to wonder who the organizer was and what experience has he had in setting up such events.

Polish media also have their fair share of blunders. In August 2018, in response to the rising popularity of secure internet messengers, three journalists from renowned Polish daily Rzeczpospolita wrote about the alleged security gaps in WhatsApp and Signal apps. The information presented in the articles came from a PR material sent to editorial offices all around the country by an agency promoting a competing product.

When communicating via email, remember about digital security. Be cautious if:

- the email address does not match the signature at the end of the message;

- the sender is seemingly trying to impersonate someone else (e.g. are there any typos or repeated characters in the address? The e-mail address differs from the display name?);

- there are suspiciously looking files attached to the message (e.g. a .zip or .rar file);

- there are any links that look untrustworthy (e.g. http: //forlossretin. tk/h53k) – do not click it!

4. Verifying Graphic and Audiovisual Materials

Even the largest media outlets sometimes goof up their photos. The problems encompass journalists getting fooled by pictures that were photoshopped or otherwise tampered with, but also their publishing of pictures unrelated to the event described, e.g. BBC portal illustrated a massacre in Syria using a photo taken some years before in Iraq.

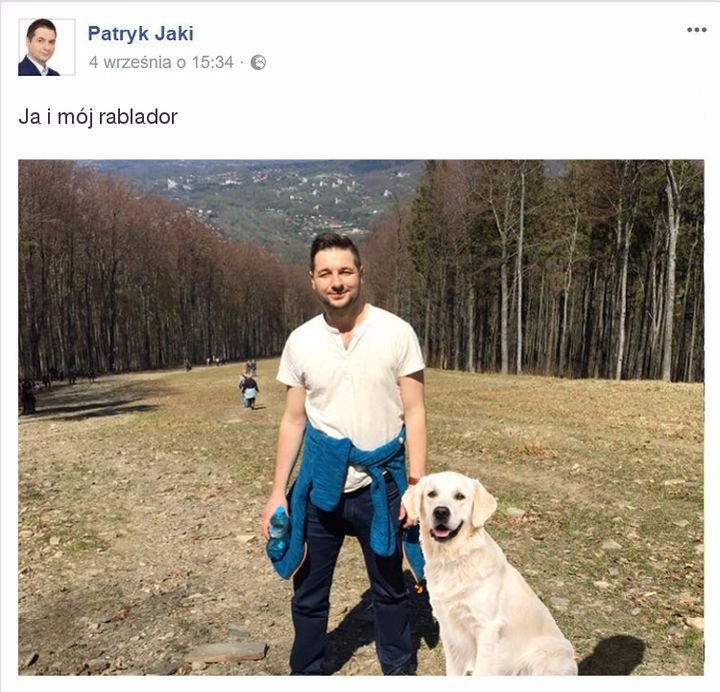

Fake Inside a Fake

Warsaw mayoral election candidate Patryk Jaki's slip-up about the German 'hatacumb' sparked the imagination of journalists from ASZdziennik.pl satyrical portal. For comedic purposes, the team photoshopped a dog into the politician's photo. The montage was subsequently used in local elections campaign (against Jaki), along with the accusations that Jaki allegedly manipulated the picture himself in an effort to 'warm up' his image in the eyes of Warsaw voters.

Source: ASZdziennik

When verifying photos and other graphic materials always remember to:

- Check metadata, the information about where, when and with what device the picture was taken. Next, compare it to the circumstances it depicts. Only original photos allow you to do that: photos uploaded to social networks are stripped of all metadata. Therefore, if you receive a picture you are about to publish from such source, ask for the original file sent through different channels, e.g. by email.

- Use the reverse image search, enabling you to check where else a specific image appears on the Web, such as TinEye.com or RevEye.

Authentic Photo – Manipulative Comment

In April 2019, the reports about the Notre Dame fire in Paris exploded all over the global news. In Russia, the Sputnik portal published an article with a photo of two men leaving the scene of fire. The photo quickly spread all over the Internet along with a comment ‘The Muslims are laughing while Notre Dame is burning down’.

Investigative journalists took a closer look at the account responsible for the publication. It turned out to be full of anti-Muslim narratives, leading the journalists to believe that the photo has to be a fake; as it turned out, prematurely. They corrected their mistake right away. LeadStories experts confirmed the authenticity of the image after analyzing its metadata, circumstances of publication (how fast after being recorded did it appear on the portal) and comparing the details seen in the photo with another material captured with the same device. As it turned out, the only part manipulated was the comment. In a published interview with the two men, the AFP eventually confirmed that the motives ascribed to them had no basis in fact.

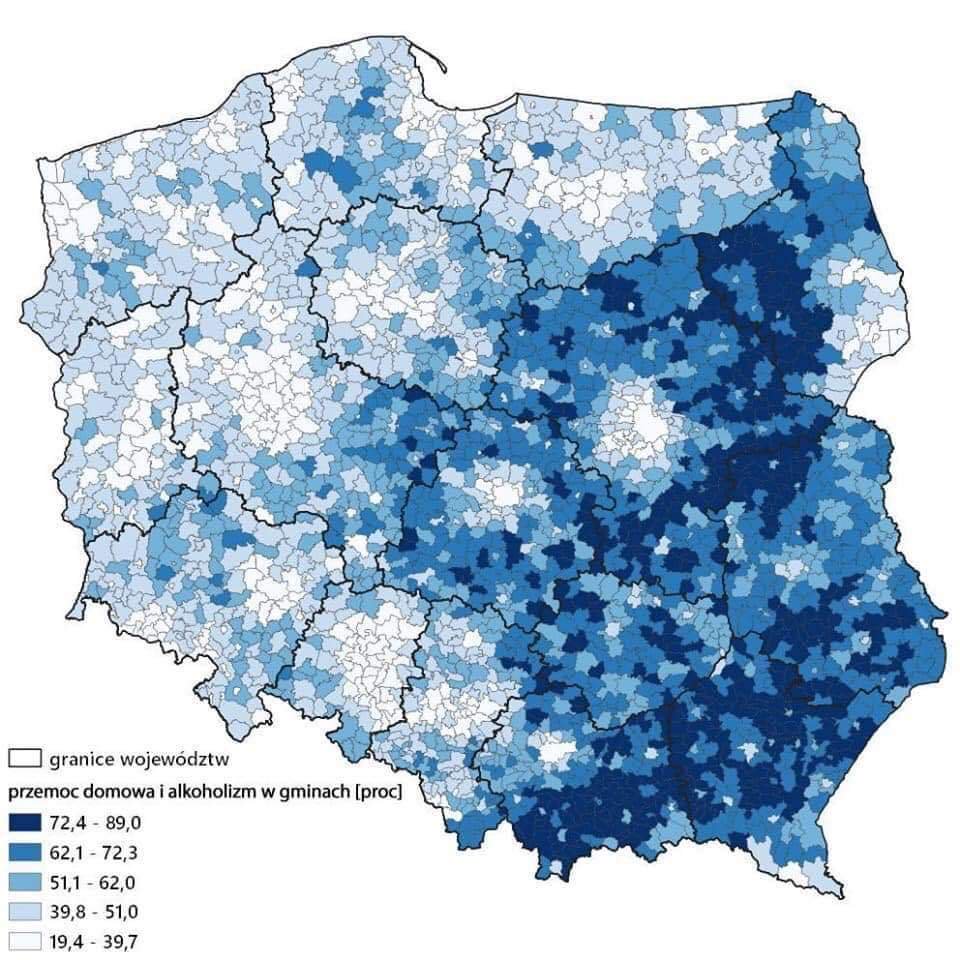

Real Map – False Description

In May 2019, moments after the publication of the European Parliament election results in Poland, a map was circulated around Polish Twitter, Facebook and Instagram; attached to the map was a description suggesting a correlation between voting for Prawo i Sprawiedliwość [Poland’s ruling Law and Justice party, PiS] and instances of domestic violence and alcoholism. The ‘news’ was analyzed by the staff of Konkret24 fact-checking portal.

According to a suggestion by one of the users who posted in the comments section, the original graphic could be found on the website of a company specializing in preparation of maps and analyses. The map turned out to depict the support for PiS committee in the last election to the EP and has been based on the data provided by Poland’s National Electoral Commission.

Attempting to verify the map, the journalists from Konkret24 used reverse image search, thanks to which they tracked the site where the graphic was originally published simply illustrating the outcome of the election. After verifying the data and correlations between variables, they debunked the primary thesis. The alleged links to domestic violence and alcoholism were only a figment of a Twitter user’s imagination.

New technologies (including Artificial Intelligence) can now be used to generate increasingly convincing montages (aka deep fakes) from recordings of public persons freely available online. Thus, ‘Nicholas Cage’ starred in an Indiana Jones movie, ‘Barack Obama’ warned against fake news and ‘Mark Zuckerberg’ described how he plans to take over the world. In a slowed-down recording of the US congresswoman Nancy Pelosi, she appears to be drunk or ill.

Verifying video content is technically harder than verifying photos. First of all, look at the video itself and the contexts in which it appears, and then ask yourself:

- Does the video contain an obvious manipulation? How probable is it that a given person would actually say something like this? Is there a sensational feel to the video, but no source and basic information on who published it and where, how, when and to what end was it published?

- Does the video look like it has been altered? Can you spot any distortions, are the audio and lip movement out of sync?

- Are there any discrepancies between descriptions by different users sharing the video? For example, do they agree on where it was shot?

- What is the source of the recording? Who uploaded it to the Web?

Crime Scene Evidence

In June 2018, a recording of soldiers executing two women with children surfaced on the Internet. Amnesty International blamed the killing on the Cameroonian army, which the country’s government disavowed. The recording was inspected by the BBC’s Africa Eye staffers, who published a response with a step-by-step analysis or the murder video. The team made use of tools like satellite imagery, allowing them to compare the distinctive topographical features (mountains, trail, trees) and pinpoint the exact place, where the tragedy happened. Next, they determined the time of day when it occurred using SunCalc app.

After conducting such analysis, you are ready to reach for technological tools.

- InVid plugin added to your browser will allow you to check whether a film from Facebook/Twitter/YouTube has been tampered with. Alternatively, you may want to try out YouTube Dataviewer endorsed by Amnesty International, which gives you access to the precise time and date of the YT videos publication.

- TinEye is designed to find out whether separate frames from the movie (screen-captured with your phone) were used before in another context.

- VLC video player has the option to slow down the recording, making it easier to spot a montage.

Additionally, you may want to analyze:

- file metadata (using your operating system’s file explorer);

- location where the video was recorded (Google Earth);

- length and direction of shadows at the place of the recording (SunCalc).

5. How Not to Fall into Out-of-Context Data Trap

Taking information out of context in order to prove one’s thesis is a timeless classic of manipulation. Vehicles of deception include videos and photos, but also established facts, such as statistical data. You can deal with this problem by:

- contacting the source from which the information came and discovering the context in which it initially appeared;

- consulting a credible expert, who will help you interpret the data.

The Lone Statistic Pitfall

Germany has the highest number of air pollution-related deaths in the entire EU – posted a certain Polish journalist and publicist on his Twitter account. Then he continued: 44% more deaths than in Poland. This entry completely ignored another statistic: the ratio of mortality to overall population size. Martin Armstrong from Statista.com portal, where the elaborated data came from, protested this misuse as follows: Germany is the most populous country in the EU, so it should not come as a surprise that the total number of deaths registered – 62,300 people – is also the highest in Europe.

Chapter II. Countering Online Disinformation

1. Media in Post-Truth Era

The importance of media in fighting disinformation cannot be overstated. On the one hand, they can debunk false and manipulated information; on the other, they can raise the level of the debate by practicing reliable journalism and building trust among their audience.

However, Polish people trust the media less and less. In 2018 and 2019, 48% of citizens declared that they trust the media, compared to 53% in 2017 and 55% in 2016. The data gathered in Poland reflects the situation around the globe. Conducted every year in more than a dozen countries around the world, Edelman Trust Barometer survey indicates that the mean level of trust in the media stands at 47% (though, unlike the Polish results, the number actually rose by 3 percentage points compared to the last year). According to the Digital News Report, covering the situation in almost 40 countries, only 44% of people (mere 2 percentage points more than the previous year) trusted the media in 2018 . In 2019, the trust level again dropped to 42%.

At the same time, professional media are rated as much more trustworthy and immune to disinformation than e.g. social media, which in the last few years became an important source of information for the public. This is especially true of Facebook, although due to doubts about the credibility of published content this platform also keeps losing trust. Research also suggests that when comparing traditional media, the local outlets command more trust than national ones. People also tend to trust more in online media that have ‘traditional’ counterparts (e.g. a printed newspaper) than those operating exclusively on the Web.

| I don't lack anything | 34% |

| reliable information (news) | 24% |

| reliable opinion | 20% |

| reliable analysis | 13% |

| good culture news and entertainment | 9% |

Research indicates that a large group of recipients is looking for reliable publications. How do they rate the credibility of information? Danae’s Trust in media. Information sources and their verification conducted for Press Club Polska and AXA in 2017 showed that key factors in building trust are: opinions from independent experts (59%), support from scientific research (51%) and consulting multiple information sources (46%). Addressing the context of a problem, neutral language or even popularity of the source are less significant.

In social networking reality, the credibility of information and users’ engagement in promoting it further depends more on the reputation of the person sharing it than on the medium that compiled it in the first place. The American Press Institute’s inquiry demonstrated that when press materials prepared by an established news agency were posted on social media by a user considered trustworthy by their audience, 52% of the recipients were inclined to rate the story as credible. Conversely, when the same publication was shared by a user commending less trust, the perceived integrity dropped to just 32%. When the authorship of the release was ascribed to a made-up medium and shared by the trustworthy account, the credibility rate again rose to 49% of users.

Publishing verified and dependable information has always been the foundation of building trust. However, the changes in recipients’ habits of acquiring information (like the turn from analogue sources to the Internet) created new challenges for the editorial offices, having to establish practices compatible with the digital age in order to convince audiences of their credibility. In this part of our manual, we present a number of techniques that will help you deliver reliable communication to your viewers more efficiently through debunking false and manipulated information, increasing the range of reliable news to the point that it becomes more widespread than fakes and implementing strategies aimed at boosting the editorial staff’s credibility, which in the long run is a crucial element of effectively combating disinformation.

Some of the proposed practices can be implemented by every journalistic professional independently. Most of them, however, concern changes practicable only with the full commitment of the staff and dependent on its size and modus operandi. If any of the solutions turns out to be inadequate, you can try to modify it or implement it to a limited extent.

2. Effectively Conveying a Revised Story

Supplying an alternative explanation of facts alone will not change the minds of those people, who already bought the disinformation. In some cases, the efforts to put the story straight only serve to further entrench erroneous convictions. Is there a way to avoid this trap?

The Debunking Handbook by John Cook and Stephen Lewandowski describes 3 ways to effectively cripple a false story.

- Do not reinforce the myth. Instead of concentrating on the myth and likely strengthening it in the process, stick to the key facts. Do not mention the myth in the headline, providing crucial and correct information instead.

- Warn against lies in advance. Every time you give an example of a myth, be sure to signal its appearance first, e.g. by adding a caption like ‘Look out! What you are about to read is not true!’. Similarly, instead of simply copying a photomontage, paste a visible ‘FALSE’ warning, instantly alerting viewers to the fact that they are dealing with a lie.

- Fill the void left by the myth. Debunking a myth should be accompanied by a reliable explanation of the underlying facts. If you are putting the source of information into doubt, make sure to give your rationale to the audience.

Remember that an overabundance of information and undue complexity are not conducive to debunking myths.

- Choose 3 essential facts you want to convey. Use simple language and short, clear sentences. Avoid emotional statements and judging.

- Adjust the communication to recipients’ level. Create several versions of your argumentation: easy (simple language illustrated with graphics), intermediate and advanced (progressively including more technical vocabulary, details, sources etc.).

If the information you shared turned out to be false, update it as soon as possible and explain why the error occurred in the first place.

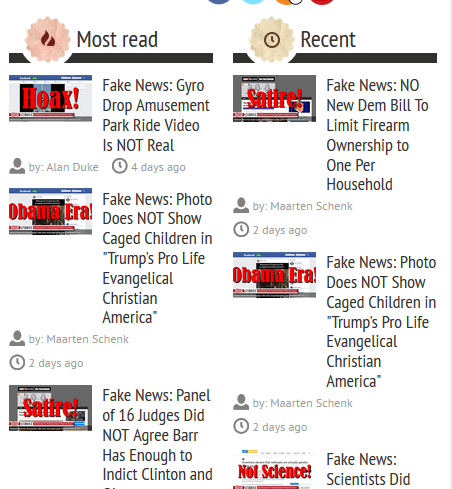

Fact-Checking Portals

Creative methods of delivering true stories are becoming more prominent over the Web, thanks to a growing number of fact-checking portals, in English (e.g. Snopes.com, PolitiFact.com, Bellingcat.com), and other languages (e.g. Polish Mitologia Współczesna, CrazyNauka czy Konkret24). You can also find examples of good practices in verifying materials documenting crimes and violations concerning human rights provided by the Digital Verification Corps under Amnesty International and in cooperation with the Investigations Lab of University of California Berkeley’s Human Rights Center.

All of those portals explain in minute details why the information is false and what really happened. Their distinctive approach is characterized by abundance of explanatory photos and screenshots, showing the viewer what to look for. Some teams, like the earlier mentioned BBC’s Africa Eye, provide their explanations in the form of videos.

3. Ensuring Reliable Communication and Showing Credibility

Credibility of press materials in the eye of the public is still influenced by traditional trust factors (see above). Keep this in mind and remember to:

- present the opinions of independent experts and authorities in the field. Providing a commentary from an expert commends more trust than only presenting the standpoints of both sides of the argument (e.g. during a political dispute) on which you are commenting (watch out for the ‘experts of all trades’ – see the paragraph on information verification in Chapter I);

- refer to scientific research, but be wary of pseudoscience – citing scientists or research and learning institutions with bad credentials can effectively sink your story;

- inform the recipients about the limitations concerning the scientific research in question, e.g. resulting from chosen scientific method (this point was confirmed in a study about hedging the reports on cancer treatment research)

- include different sources of information and multiple points of view – presenting the story from various angles will shield you against accusations of bias and will make your content relatable to a wider audience;

- report directly from the thick of it – emphasize that yours is the firsthand account and not a story written from behind the desk (you were on site, talked to the people featured in the story, you witnessed the occurrence etc.).

an example of caption added to the original text, summing up different spins on the story

Earning the Trust

During the course of our debunking workshops conducted for journalists we brainstormed some additional ideas for increasing the publications’ credibility:

- when publishing a video, add a note describing the process of creating the content;

- include an interview with the author;

- set up a live chat or a webinar with the author, allowing recipients to ask questions concerning the publication history.

Establishing credibility might also benefit from various technicalities associated with news publishing. See that:

- the materials are signed by the author;

- all the corrections, changes and updates on your website are visibly announced. Preferably, avoid the mistakes that could undermine your credibility, but when they do happen, be sure to correct them as swiftly and transparently as possible. Make clear what has been revised (e.g. by striking through the erroneous information). You can also attach errata at the end of the release;

- the original date of publication is included and that archival materials are clearly marked in case their content is out of date – using outdated information or photos from the past in a changed context is a manipulation technique frequently employed on the Internet. Clearly disclosing the time of release will limit the risk of someone misusing your materials;

- the communication is concise and straightforward – on the Internet, more than in traditional media, these factors turn out to be more conducive to building credibility;

- the ads displayed on the site are non-invasive, the website loads fast enough and is compatible with mobile devices – such technical implementations (not incidentally associated with SEO) have more influence on credibility ratings than, for instance, allowing the recipients to comment under the press materials.

Your audiences can help you gain trust by becoming involved in promoting your medium and become its ambassadors. The more trustworthy considered the user sharing your information, the more likely his recipient base will perceive your publication as plausible and become actively engaged in spreading it further (see above). It pays off to actively communicate with your viewers.

- Be active both on your website and social media. Today, social networking portals are an important channel for reaching the public, but remember – you have no control over how and to whom they distribute your content. Do not limit yourself exclusively to social media presence. Regardless of the communication channel, always post only verified and concrete information, avoiding insinuation and gossip.

- Respond also to the negative comments: this way you not only have a chance to convince skeptics, but also to show your regular audiences that you can be trusted and able to convincingly dispel doubts voiced by your critics (read about dealing with attacks and hate online in Chapter III).

- Give your readers an opportunity to contact you directly online (e.g. through webinars) as well as in real life (e.g. invite your audience to the office or organize events where they can get to know your medium better).

Building Editorial Credibility – Good Practices

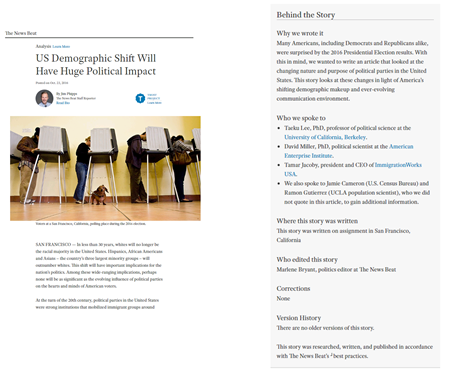

Trust Project, an organization based in the US, developed a list of 37 trust indicators, designed to facilitate the evaluation of a given medium’s credibility for the recipients. Editorial staffs introducing them to their websites are also encouraged to place a TrustMark on their main page. Trust Project recommends, among other practices, including the behind-the-scenes explanation (so-called ‘index cards’) to the release, documenting how it was prepared.

Trust Project also works towards increasing the visibility of the internet media implementing its policies on platforms such as Google, Twitter, Facebook and Bing. Nowadays, these portals became key intermediaries in accessing press publications and thanks to the indicators of trust their algorithms are supposed to automatically recognize and promote credible media participating in the project. Translated into Internet reality it means that the information portals considered trustworthy will be listed higher on Google search results and have a wider range on Facebook.

Trusting News is another initiative working toward this goal. On their website you will find not only practical advice on how to strengthen your credibility, but also an option to book an individual ‘training session’, which will help you plan your personal strategy of establishing trust toward a medium in the digital age. Concurrently with the premiere of a documentary film Putin’s Revenge, the staff of PBS Frontline published unedited interviews with people featured in the movie along with a searchable database. The recipients were thus able to check the broader context of previously seen statements and verify whether or not they were manipulated.

The Toronto Star editorial board publishes a weekly column divulging various aspects of their journalists’ work (e.g. “How do we decide which story to choose?” or “What is the policy for publishing anonymous materials sent to the paper?”).

Source: The News Beat, US Demographic Shift Will Have Huge Political Impact

4. Establishing Recipients’ Trust Toward Your Editorial Team

Increasingly often, a well written press story is not enough to reach our target audience and gain their trust. Protect your relationship with the viewers by closely inspecting whether your website raises any doubts about the editorial team (see Chapter I on what mistakes to look for). Many experts also point to the importance of augmenting the transparency of media industry by e.g. introducing the public to what is going on behind the scenes of publication and the inner workings of the editorial office.

As another good practice for your editorial website, you may want to publish:

- basic information about the medium, like ownership structure, the makeup of your team, financing (including received contributions) and founding date;

- contact information;

- labels for different types of content – facts vs opinions, visible identification of paid ads and sponsored content; even if the law in your country does not impose such an obligation, it is good to introduce mainly from the standpoint of credibility;

- a field for reporting mistakes and a list of policies concerning the publication of corrections and retractions – again, even if the law in your country does not impose it, your readers should know that your team is not afraid to admit mistakes. Let them know how they can report an error and how the resulting changes are published. Also, consider creating a repository of corrections and rectifications;

- information about the values and principles embodied by members of your team including editorial line, mission statement, ethics of selecting information and cooperating with anonymous sources. Show some examples of releases which the editorial staff is most proud off and which clearly represent its goals (e.g. those which brought about positive changes);

- comment moderation policy (both for the website and social media). Inform clearly about the criteria employed by your staff when deciding which comments to publish and which to stop. Specify the types of content that will not be tolerated, whether commenting requires registering first, the use of any automatic filters, and the ways (if applicable) to appeal the decision of the moderator).

We also recommend appending each release with additional information on:

- the author – include a short biographical note, their picture, role on the board, links to other publications, information about competencies in a given field (have they researched it or written a book about it?), and indicate any possible conflict of interest;

- the author’s reasons for preparing the publication – what did they intend to achieve, why have they chosen this particular story etc. This can prevent conspiracy theories from forming around the publication in question;

- details concerning preparation of the materials – who did the author interview, which sources have been used, what did the fact-checking look like and where exactly was the article created. This kind of information is especially useful when dealing with larger, more in-depth publications (e.g. reportages) and particularly important and controversial topics.

5. Ensuring Credibility During Elections

The journalist’s work in the period before the elections is fraught with legal restrictions and communication challenges. The basic condition for retaining credibility is not combining working as a journalist with running in elections. Meanwhile, the editorial board should oversee that:

- the materials received from electoral committees are clearly marked – you have to make evident that each ad and all other kinds of political content is sponsored by a particular committee and does not originate from your medium;

- the medium is available for all parties and candidates, for instance by posting publicly your pricing scheme for political advertising;

- the reports on public persons running for office are prepared with utmost caution. The candidates, especially those already holding a public office, have a number of opportunities to cast them self in a positive light during various functions (such as cutting a ribbon at an inauguration of a new pediatric ward in a local hospital or announcing the renovation of a school’s sports field). Such news should be reported in a way that restricts the possibility of misusing it for publicity purposes.

These rules are as important in the case of main platforms of content distribution for a given medium (newspapers, websites) as for social media and messaging apps; they apply to both the entirety of the staff and each journalist in particular.

Chapter III. Protecting Yourself from Retaliation After Debunking a Fake Story

1. Journalists Under Attack: A Threat to Media Freedom

Exposing disinformation often reveals truths inconvenient for some people, which might result in a number of threats to media workers. Working as a journalist, you have to be aware that your work will be criticized. Unfortunately, a lot of times the reactions to press releases are not aimed at disputing facts or opinions, but rather creating a hostile atmosphere and silencing troublesome voices.

Persons and entities that risk being exposed may threaten to take legal action or obstruct access to information by, for instance, not letting journalists into local council meetings. However, it was online attacks that the participants of our workshops were afraid of the most. Online acts of aggression include brutal verbal harassment, threats, circulation of false or manipulated information, revealing private information, hacking a publisher’s website, identity theft and many more. Compared to their male counterparts, female reporters are more often subject to cyberbullying targeting their looks, gender or private life. Tactics such as posting sexually-charged comments, images with photoshopped sexual content or even threats of rape are aimed at casting doubt on their qualifications and intimidating them.

Debunker Targeted by Smear Campaign

In 2014, Finnish journalist Jessikka Aro conducted an investigation uncovering the so-called ‘troll factories’ in Russia, which were disseminating pro-Kremlin propaganda and disinformation on the Web. The trolls retaliated by attacking her on social media. Fake videos featuring her look-alike were spread across the Internet to convince people that she had a drug problem. She was also threatened and one time harassed by someone pretending to be her long-dead father. Her home address and health information were posted online.

Source: Jessikka Aro's Twitter

In the end, the perpetrators did not escape justice. In 2018, a court in Finland convicted two persons responsible for cyberharassment against Aro (the first offender was sentenced immediately to 22 months in prison, the second to 12 months [suspended]) and ordered them to compensate the journalist with 90,000 euros.

Over 40% of journalists reported having become a target for various attacks related to their profession at some point during the previous 3 years, out of which 53% takes form of cyberbullying. Nonetheless, at the time 57% of responders did not report to anyone about being victims of online violence. All of this poses a serious challenge for dependable journalism, since sense of security is one of the key conditions necessary for uncovering manipulation. Lack of security contributes to the so-called chilling effect: the reluctance of media workers to tackle contentious subjects out of fear of suffering negative consequences. Some of the questioned journalists scaled down reporting on certain topics, while some even abandoned working on certain cases

Aggression more often hits journalists working on the topics controversial in the given community. E.g. according to the International Press Institute, Polish journalists are especially vulnerable to online violence when publishing information on matters like national politics, refugees, Polish-Jewish relations, equality for women, gender-related issues or reproductive rights.

It is impossible to fully protect yourself from a threat of online attack. However, in some cases you can reduce the risk of being affected and prepare yourself for when it finally happens. We divided the proposed countermeasures into two categories: the ones you can implement yourself and the ones that will require the involvement of entire editorial staff.

2. Online Violence Prevention for Journalists

Securely managing information online is the best way to minimize the risk of attack. Nonetheless, it is not enough to install a few apps and have your computer ‘set up by an IT guy’. In this case, consistency and alertness are as important as technical competencies.

If you want to protect yourself against attacks on the Web:

- Protect the access to accounts and services you use: secure them with strong passwords and, whenever possible, switch to two-factor authentication. Change your passwords regularly and store them safely where only you can access them.

- Be careful about revealing your personal information online. Do not post private information on social media profiles, especially about your family (e.g. children) and other sensitive facts. If you decide to do so anyway, be sure to restrict the number of people who can view them, for instance by separating your acquaintances into groups with different levels of authorization (e.g. on Facebook) and regularly check your friends list.

- Never share your localization: disable it both in your mobile devices and apps and portals you visit, particularly when conducting field research.

- Adjust privacy settings on your device. Restrict potentially vulnerable programs’ access to your localization, camera and microphone, block tracking cookies and scripts on your browser and do not sign in to your account when working on a press release.

- Implement preventive measures in your smartphone. Phones and other portable devices are much easier to lose than your desktop computer, which is why it is of utmost importance to secure them properly, e.g. by setting up a six-digit passcode on your lock screen, encoding your hard drive, deleting unused apps and disabling connections with public Wi-Fi networks. Not all resources should be accessed from the phone; you should connect to your medium’s cloud drive or download encrypted emails at work or home.

3. Online Violence Prevention for Editorial Staffs

The editorial team has even more options for preventing cyberbullying, which is why you might want to encourage decision-makers at work to take action. Show them this manual, convince to set up a meeting with an expert or organize a workshop about countering online attacks; point to the examples of good practices, inspiring your co-workers to implement them. Emphasize the importance of building trust and credibility – these efforts will pay off should your medium come under attack.

The most important preventive strategies your team should introduce:

- Risk assessment: consider who at your office might be especially vulnerable to attacks, what types of aggression you should prepare for and how it will affect your work. Conduct a survey to get to know your co-workers experience with Internet violence and regularly come back to this issue during staff meetings. Only when the threats have been clearly defined you can effectively consider possible countermeasures and crisis management. However, always remember that threats tend to change and a once-established policy requires regular verification.

- Training journalists in secure information management – try the resources recommended by the International Journalist Network.

- Policy training for managing website and social media comments:

- Begin with a clear policy defining the rules of discussion (see above).

- Implement the good practice of outsourcing the moderation of comments to a person uninvolved in preparing the materials, especially when you are expecting a backlash of hateful comments. An outsider will have more distance when reacting to such posts and the author will be better protected from hate.

- Several news websites disable commenting for unregistered users. This requirement may limit the number of hateful comments; at the same time, it creates a risk of losing the voices of those good-willed users, who do not want to submit their data or waste time on setting up an account.

- Some publicists (among them Spiegel Online) experiment with algorithms designed to identify hateful and unsubstantiated comments. Nonetheless, this solution also has its limitations: the algorithm is far from infallible and requires constant supervision of an employee.

Checking Posters’ Reading Comprehension

Todd Rogers, an American psychologist, has proven through his research that people have a tendency to express more radical opinions when they have a subjective sense of understanding a given problem or having knowledge on the subject. When confronted with questions designed to force them into finding a real explanation, however, they often change their statements to less extreme, realizing they knew less than they thought they did.

This conclusion was then creatively employed by Norwegian broadcaster NKR to limit unsubstantiated, hateful comments under published articles. To be able to leave a comment, the reader now has to correctly answer three questions about the content of the publication first. This serves to ensure that they did read the article and understood it, and not confined themselves to just skimming through the title and lead. The experiment is still underway and the staff positively evaluates the first results.

- Providing technical support. Even small media outlets should employ a full-time IT staff, ensuring proper configuration of networks and software and quick response in case of an attack.

- Introducing information security procedures, e.g. using separate room for staff meetings and work, providing journalists with safe equipment (avoid sharing computers), locking up the server room or guarding the access to a shared drive.

- Raising consumer awareness. Reporting on the problem of online attacks should become a fixture of your medium’s communication. Journalists shaping social awareness and sensitivity to harmful practices and their potential consequences for victims and perpetrators alike, are contributing to eradicating the issue and increasing their capacity to offer support to their recipients who fall prey to cyberbullying.

4. Damage Control for Journalists

Not all attacks can be prevented. If you are affected by online aggression:

- Document and monitor. Take screenshots or start on a so-called ‘hate journal’, where you can write down the time, place, hateful content and its creators. These materials may be helpful if it comes, for instance, to taking legal action (see below). Monitor the internet using advanced browser features or Web-monitoring tools (Brand24.pl, Google Alerts) set to scan for your name, phone number or other information.

- Rebut the accusations or report harmful content. One of your better options is to address the attack on the same communication channel. However, if that channel is exceedingly hostile, you may choose to report it to the website’s or social network’s administrator as soon as possible (e.g. in Poland, if the reported content is found to be against the law, the administrator is obliged to take it down immediately). You can also apply for free help to organizations fighting harmful online content in your country (e.g. in Poland Dyżurnetu or HejtStop – search their websites for instructional videos explaining how to report harassment). They might prove exceptionally helpful if the administrator ignores your complaint.

- Answer or block. When hateful content appears e.g. on your social media profile, there is no one universal strategy to neutralize the attack, so adjust your reaction to the circumstances. Sometimes it is enough to address the accusations in order to construct a counternarrative (preferably with assistance of others, see below). At other times, when there is no chance of an informed discussion, it is better to ignore the hater (following the rule of ‘not feeding the troll’). However, in some instances – especially when the attack is extremely brutal – the only option is to block the attacker. Hateful and manipulated stories targeted at journalists are oftentimes a part of coordinated campaigns employing social media bots or fake accounts. Exposing them may help you block them and further defend yourself (use the pointers from Chapter II).

- Do not hesitate to ask for support. Make sure to inform your editorial board and its lawyers. Consider telling your family that you have become a target of persecution before they find out about it from outside sources. Also, do not forget about your co-workers and acquaintances – dealing with online attack on your own might prove exhausting. Ask others for support. If you have such options, consider involving people around you in monitoring and documenting the attacks, reporting hateful content and taking matters to court. Above all, however, put them in touch with your haters. Appeal to your readers to come to your aid. Be aware that Internet violence victims, especially when continuously exposed to a barrage of hate, pay real price in their private lives; they can experience depressive mood swings, depression, anxiety disorders and more. If any of the above applies to you, think about consulting a specialist.

- Exert your ‘right to be forgotten’ in the search results. If someone unlawfully publishes information about you, you have the right to request from the search engine providers that they remove the links to those publications after your personal data was typed into the search bar. That does not mean that unwanted content will disappear from the Web, but it will be much harder to access and there is a chance that when researching your person, people will not stumble upon malicious manipulation. If a search engine operator declines your request, you are entitled to file a complaint to the Data Protection Authority in your country. Do not forget – you should not use the right to be forgotten to cover up inconvenient facts about yourself.

- Take legal steps. Depending on the nature of the harmful content online, you can refer to:

- criminal law (such as hate speech, stalking, insult or defamation laws). In case of pubic prosecution crimes all you need to do is to report it to your local police who should then investigate the case; or/and

- civil law (such as libel or image rights); or/and

- data protection law (in the EU – GDPR and domestic data protection laws – in case of misuse of your personal data on the Internet you can seek help from your national Data Protection Authority).

The State’s Responsibility: Effectively Protecting Journalists

Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismailova is known for her uncompromising efforts to reveal the abuse of power by public servants in her country. She was recorded in an intimate situation with her partner. The authors of the recording threatened to post it online if the journalist continued to work on publications concerning a corruption scandal allegedly involving people connected to the government. Ismailova did not cave and instead decided to publicize this instance of blackmail in order to prepare the public opinion for the eventual disclosure (in the end, the recording made its way to the Internet) and to notify the police.

Photo by Aziz Karimov [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Unfortunately, the Azerbaijani law enforcement agencies failed to identify the perpetrator and the journalist had to seek justice in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. The Court accused the Azerbaijani government of not conducting a proper investigation and declared that it did not take sufficient action to protect the journalist’s right to privacy, as well as her freedom of speech (considering that the blackmail was calculated to discourage her from continuing her journalistic investigation). The journalist received a compensation of 15,000 euros. Therefore, through this verdict, the Court has confirmed that it falls on government agencies to protect the media employees from attacks (including those perpetrated online) and to employ adequate measures in investigating the circumstances in all such instances.

5. Damage Control for Editorial Staffs

The editorial team’s reaction to online attacks is exceptionally important. The measures taken in those cases include:

- Ensuring organizational, psychological and legal support: as editorial staff, you should designate and thoroughly train a person to whom the attacked journalists may turn, should the need arise. This employee should be responsible for situation assessment (which can be very difficult for the victim), preparing a strategy to deal with the attacks and then implementing it. If your editorial team can afford to introduce such rapid response system, it might be beneficial to pitch that idea to journalists’ or publishers’ associations and convince them to apply it on an inter-editorial scale. This could take form of a helpline, where people could receive help from experts. Journalistic organizations are also a useful forum for sharing experiences and good practices concerning cyberbullying.

- Publicly defending journalists: the editorial office should introduce a policy of supporting the team members who were attacked on the Web and encourage other journalists to do the same. You must analyze the circumstances first – while the proposed solution may be effective in cases of brutal, coordinated of mass cyber violence, in less hostile instances it may only serve to further publicize the issue.

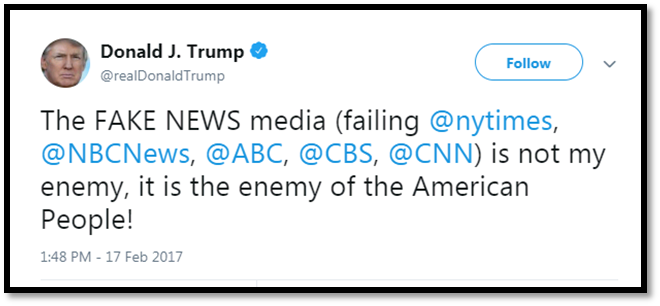

Media Under Fire: When ‘Fake News’ Becomes a Label

President Donald Trump does not hesitate to call the biggest American media ‘fake news factories’. This strategy of separating oneself from inconvenient realities and discrediting a journalist revealing them is employed all around the world, including Poland. Instead of demanding corrections or starting libel suits (where you have to substantiate your accusations and fulfill formal requirements), a politician simply has to go on social media and accuse a journalist of spreading ‘fake news’. In the US, over 400 editorial offices got involved in an initiative started by the Boston Globe newspaper and published articles protesting Donald Trump’s attacks on media.

Further Reading

- American Press Institute, A new understanding: What makes people trust and rely on news

- American Press Institute, ‘Who shared it?’: How Americans decide what news to trust on social media

- Data & Society, Reading Metadata

- Data Driven Journalism, A primer on political bots – part two: Is it a Bot? It’s complicated!

- European Journalism Observatory, How Trust Is Being Rebuilt In Germany’s Media

- Exposing the Invisible, The Kit: How to See What’s Behind a Website

- Fundacja Panoptykon, Odzyskaj kontrolę nad informacją. Samouczek dla dziennikarzy i nie tylko

- Helsińska Fundacja Praw Człowieka, Wiem i powiem. Ochrona sygnalistów i dziennikarskich źródeł informacji

- International Fact-Checking Network, 10 tips for verifying viral social media videos

- International Fact-Checking Network, A 5-point guide to Bellingcat's digital forensics tool list

- International Press Institute, Measures for Newsrooms and Journalists to Address Online Harassment

- Knight Foundation, Crisis in Democracy. Renewing Trust In America

- Knight Foundation, Indicators of News Media Trust

- PEN America, Online Harassment Field Manual

- Press Club, Zaufanie do mediów. Źródła informacji i ich weryfikowanie

- Reporterzy bez Granic, Online Harassment Of Journalists. Attack of the trolls

- The Nieman Reports, 6 Things Journalists Can Do to Win Back Trust

- The Nieman Reports, Can “Extreme Transparency” Fight Fake News and Create More Trust With Readers?

- The Trust Project

- Trusting News Project, Helping journalists earn news consumers’ trust

- Authors:

- Dorota Głowacka, Anna Obem, Małgorzata Szumańska

- Co-operation:

- Beata Biel

- Translation:

- Stanisław Arendarski

- Web design:

- Marta Gawałko | Caltha

Panoptykon Foundation, Warsaw, August 2019

Licence: CC BY SA 4.0

Deadling with Disinformation. A Handbook for Journalists was prepared by Panoptykon Foundation. It's a result of a project carried out in co-operation with the Reporters' Foundation “Elections without Disinformation”, which included a series of workshops for journalists from local and national media, bloggers, activists. The project was realized in co-operation with Heinrich Böll Stiftung in Warszaw and Google Poland.

Panoptykon Foundation keeps an eye on public authorities and business corporations. We intervene to protect human rights, we advocate for better law to protect freedom and privacy. We show how to make conscious choices in the more and more digital world.

Reporters Foundation teaches and supports journalists in the Central & Eastern Europe and pursues development of the investigative journalism.

Want to support our work? Donate to Panoptykon and Reports' Foundation!