INTRODUCTION

Beginning in 2018, on the heels of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, conversations about the scale and impact of political microtargeting (‘PMT’) began to significantly fuel the newscycle and shape the political agenda. The EU began its war on disinformation and convinced leading internet platforms, including Facebook, to self-regulate. As a result, internet users were offered new tools and disclaimers (see: Facebook moves towards transparency) meant to increase the transparency of targeted political ads. Researchers rushed to analyse data from Facebook’s ad library, hoping to find at least some answers to the very troubling questions raised by the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

These questions included: Is it possible to target people based on their psychometric profile, using only Facebook data? Under what circumstances does PMT have a significant impact on voters? How does PMT differ between the U.S. and Europe, given Europe’s more modest advertising budgets, stronger legal protections, and varied political cultures? Does the use of PMT call for new legal rules? Are we ready to name concrete problems, and identify which of them can be solved by regulators? And last but not least: Who should be the target of such regulation? Political parties and their spin doctors, because they commission targeted ads? Or Facebook and other internet platforms, because they deliver targeting results and build the algorithms, or “magic sauce,” that make it all possible?

Polish and European political momentum

With these questions in mind, Panoptykon Foundation, ePaństwo Foundation, and SmartNet Research & Solutions (all based in Poland but operating in international networks, see: About us) embarked on a joint research project titled “Political microtargeting in Poland uncovered: feeding domestic and European policy debate with evidence”. The project started in spring 2019 and was funded by the Network of European Foundations as part of the Civitates programme. The timing seemed ideal: Poland was in the middle of its electoral triathlon, which began with local elections (2018), continued through EU and domestic parliamentary elections (2019), and concluded with presidential elections (2020). We also cooperated with Who Targets Me to leverage their crowdsourced database of political advertisements from Facebook. (Beginning with the 2019 EU elections, the Who Targets Me plugin was available for Polish users).

Our research was based on two streams of data: data voluntarily shared with us by Polish Facebook users (via Who Targets Me plugin), and data obtained by us directly from Facebook (via their official ad library and API which was made available to researchers). Based on this data, we hoped to measure the value of Facebook’s new transparency tools as well as collect evidence on how targeted political advertising is used as a campaign tool in Poland. We believe European policy debates would benefit from more evidence on the use of PMT, especially in the light of upcoming regulation on internet platforms (the so-called Digital Services Act, to be proposed by the European Commission by the end of 2020).

Research questions and (missing) answers

When designing our research, we sought to answer a handful of important questions:

- Are voters’ vulnerabilities exploited by political advertisers or by the platform itself?

- Are there different political messages for different categories of voters?

- Are there any contradictions in messages coming from the same political actor?

- Is PMT used to mobilise or demobilise specific social groups?

- What is the role of “underground,” or unofficial, political marketing in this game of influence?

After 12 months of collecting and analysing data, we still don’t have all the answers. And we won’t have them until we are able to force online platforms, Facebook in particular, to reveal all the parameters and factors that determine which users see which ads. In the course of this research, we found the missing answers (e.g. what we still don’t know about Facebook’s “magic sauce”) as interesting as the evidence we did find. We have also discovered that country-specific regulations are not prepared for securing transparency of the election campaign. We hope that this work — in particular our recommendations — will be a meaningful contribution to the pool of research on the impact of PMT and the growing role of internet platforms in the game of political influence.

How to navigate the report

In the first part of the report, “Microtargeting, politics, and platforms,” you will find:

- An explanation of our choice to focus narrowly on PMT, given it is one of many techniques for influencing voters;

- An overview of the role of political parties, which use various targeting techniques (not restricted to PMT);

- An explanation of why online platforms, Facebook in particular, play a key role in microtargeting voters based on their behavioural data;

- An explanation of the ad targeting process and the roles that advertisers and Facebook play;

- And basic information about Facebook’s ad transparency tools and policies related to the use of PMT (self-regulation inspired by the European Commission).

In the second part of the report, “Microtargeting in the Polish 2019 election campaign. A case study,” you will find:

- An explanation of our research methodology and objectives;

- Key takeaways and collected evidence;

- Evaluation of transparency tools that are currently offered by Facebook;

- And a summary of what remains unknown and why these blind spots are so problematic.

In the third part of the report, “Recommendations,” you will find:

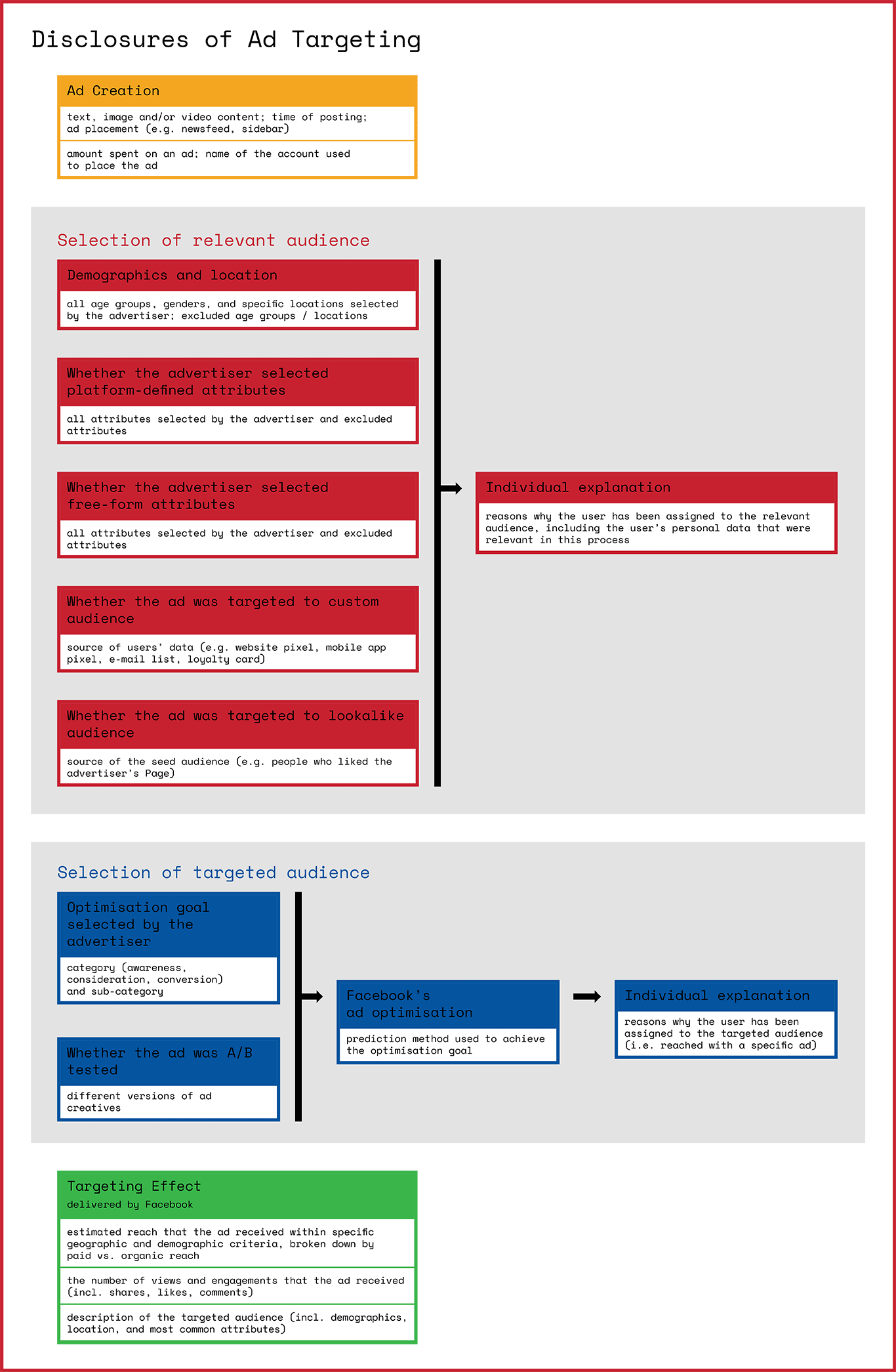

- Our recommendations for policymakers (based on our own work and the work of other researchers);

- Our interpretation of the GDPR in the context of PMT;

- Our proposition for new disclosures as well as new data management and advertising settings, which would help users control their data and manage their choices in the context of PMT.

Who is it for?

We drafted this report thinking about policymakers and experts interested in regulating PMT and transparency of election campaigns in social media, as well as fellow researchers and activists who struggle with our same questions. We are aware that this audience does not need an overview of existing literature on this topic. In the interest of producing a useful and concise report, we essentially limited its scope to the presentation of new evidence (i.e. the case study showing how PMT was used during the 2019 elections in Poland) and our recommendations, which we formulated in order to fuel the debate. Definitions, context, and explanation of the ad targeting process (Part 1 of the report) has been limited to the minimum. For those who are interested in a broader picture (going beyond the use of PMT on Facebook) or need more information about the targeting process, we have a reading list at the end of the report.

Part I. Microtargeting, politics, and platforms

1.Political microtargeting as (part of) the problem

Microtargeting and potential harms

Political campaigns increasingly use sophisticated campaigning strategies fueled by people’s personal data. One of these techniques is microtargeting: using voters’ data to divide them into small, niche groups and target them with messages tailored to their sensitive characteristics (such as psychometric profiles).

The UK Information Commissioner defines microtargeting as “targeting techniques that use data analytics to identify the specific interests of individuals, create more relevant or personalised messaging targeting those individuals, predict the impact of that messaging, and then deliver that messaging directly to them.” According to Tom Dobber, Ronan Ó Fathaigh and Frederik J. Zuiderveen Borgesius, the distinguishing feature of microtargeting is turning one heterogeneous group (e.g. inhabitants of a particular neighbourhood) into several homogeneous subgroups (e.g. people who desire more greenery in the city centre, people who use a particular type of SIM card, etc.). In the words of the researchers:

Micro-targeting differs from regular targeting not necessarily in the size of the target audience, but rather in the level of homogeneity, perceived by the political advertiser. Simply put, a micro-targeted audience receives a message tailored to one or several specific characteristic(s). This characteristic is perceived by the political advertiser as instrumental in making the audience member susceptible to that tailored message. A regular targeted message does not consider matters of audience heterogeneity.

Colin Bennett and Smith Oduro-Marfo observe that microtargeting can be conducted across a number of different variables: Not only the demographic characteristics of the audience, but also a clear geographic location, policy message, and means of communication:

The practice varies along a continuum with the “unified view” of the voter at one extreme end, and the mass general messaging to the entire population at the other. Most “micro-targeted” messages fall somewhere in between and are more or less “micro” depending on location, target audience, policy message, means of communication and so on. Thus, micro-targeted messages might be directed towards a precise demographic in many constituencies. But they may equally be directed towards a broader demographic within a more precise location. A precise and localised policy promise, for instance, might appeal to a very broad population within a specific region.

Existing research shows that political microtargeting (or PMT in this report) carries several risks related to its inherent lack of transparency. It may:

- Enable selective information exposure, resulting in voters’ biased perception of political actors and their agenda;

- Enable manipulation by matching messages to specific voters’ vulnerabilities;

- Fuel fragmentation of political debate, create echo chambers, and exacerbate polarisation;

- Enable an opaque campaign to which political competitors cannot respond;

- Be used to exclude specific audiences or discourage political participation;

- Make detection of misinformation more difficult;

- Facilitate non-transparent PMT paid by non-official actors;

- Raise serious privacy concerns.

Why we chose to focus on PMT

We acknowledge that political parties have many other tools at their disposal for influencing potential voters (see: Political parties as clients: hiding in the shadows). In this context, it is important to view PMT as one part of a much bigger picture. Nevertheless, in this report we will not look at the whole picture, but exclusively at the use of PMT. We chose this focus for the following reasons:

- Other researchers, civil society organisations, and investigative journalists are in a much better position than us to shed light on the advertising or communication practices of political actors. Our mission is to expose the practices of surveillance and the use of personal data to control human behaviour;

- Amongst many data-driven advertising practices, microtargeting — which is often based on users’ behavioural (observed) data and data inferred with the use of algorithms — poses specific threats and therefore deserves more attention as a relatively recent phenomenon in the world of advertising;

- Given technological trends such as the popularisation of smart, connected objects (IoT) and fast-growing investments in AI, it seems likely that in the coming years we will face an inflation of behavioural data and new breakthroughs in predictive data analysis;

- Unless restricted by legal regulations, both online platforms and their clients (including political advertisers) will be keen to experiment with these new sources of personal data and new predictive models in order to target ads even more efficiently;

- Facebook has already sent a strong signal to its clients that the best way to increase their audiences’ engagement on the platform is to choose sponsored content. Since Facebook’s business model is based on advertising revenue, we can expect that this trend will continue and — as the reach of organic posts continues to decline — political advertisers will be pushed to invest more money in techniques such as PMT;

- In the light of these trends, we saw the need to produce country-specific evidence on the use of PMT by Facebook (and its clients) during 2019 election campaigns, hoping to inform a pending political debate on whether the EU should introduce further regulations in this area.

2.Political parties as clients: hiding in the shadows

According to the British ICO, “as data controllers, political parties are the client for the political advertising model, and sit at the hub of the ecosystem of digital political campaigning.” At the same time, we know little about political parties’ data-driven techniques for voter analytics and political persuasion. The key problem here relates to non-transparent spending and the existence of the political marketing “underground” — unofficial actors like Cambridge Analytica acting on behalf of political parties or for their own interest. Current regulations written for traditional political campaigning do not account for problems generated by online platforms and data brokers, who are now key players in this game.

In their “Personal Data: Political Persuasion” report, the Tactical Tech Collective examines the “political influence industry” and the techniques at their disposal. The authors of the report categorise data-driven campaigning methods to “loosely reflect how value is created along the data pipeline” and distinguish three crucial types of techniques:

- Acquisition - data as a political asset: valuable sets of existing data on potential voters exchanged between political candidates, acquired from national repositories or sold or exposed to those who want to leverage them. This category includes a wide range of methods for gathering or accessing data, including consumer data, data available on the open internet, public data, and voter files.

- Analysis - data as political intelligence: data that is accumulated and interpreted by political campaigns to learn about voters’ political preferences and to inform campaign strategies and priorities, including the creation of voter profiles and the testing of campaign messaging. This includes techniques such as A/B testing, digital listening, and other methods for observing, testing, and analysing voters and political discussions.

- Application - data as political influence: data that is collected, analysed, and used to target and reach potential voters with the aim of influencing or manipulating their views or votes. This includes a diverse set of microtargeting technologies designed to reach individual types and profiles, from psychometric profiling to Addressable TV. The artful use of these techniques in unison has been touted by some campaigners as the key to their success.

In the Polish context, there is little we can do to uncover this kind of shadowy political influence, apart from looking at its online traces. Political microtargeting is one such trace. And Facebook is, at this point, the most open platform for documenting it. This realisation was one of the premises behind our research. There is, however, a second critical premise: Online platforms have their own tools of power and influence that matter in the context of political elections, and therefore should be subject to public scrutiny.

3.Facebook as a key player in the game

When we chose to focus on the use of PMT, it quickly became clear that we would also need to focus on Facebook.

In recent years, Facebook has established itself as a leader in the political advertising market. In the EU, its political advertising revenue dwarfs that of Google. According to self-assessment reports published by both companies, between March and September 2019 political advertisers spent €31 mln (not including the UK) on Facebook and only €5 mln on Google. Even taking into consideration Facebook’s broader definition of political and issue ads, the difference is immense.

While other platforms also allow for targeting users based on their behavioural data (e.g Google’s adwords are based on search results, which may include political content), Facebook has built its reputation as the most granular advertising interface. It has also boasted about its ability to match ads and users based on hidden (and sometimes vulnerable) characteristics.

In 2015, Facebook introduced the concept of custom audiences (see: Custom audience), allowing advertisers to create their own specific customer segments directly within their Facebook Ads Manager, without the need to extract the data and analyze it externally. In 2016, this feature was expanded and advertisers could also target “lookalikes” (see: Lookalikes) of their custom audience, benefiting from Facebook’s own data analytics. Since then, Facebook has been improving its matching algorithm. This effort resulted in new patents for models and algorithms, including one that allegedly allows for insight into users’ psychometric profiles based on seemingly benign data such as Likes.

In this context, it is hardly surprising that Facebook became the target of investigations after the Cambridge Analytica scandal. While media reports focused on Facebook’s ability to microtarget voters and exploit their vulnerabilities, regulators turned out to be more concerned with “security breach” — that is, allowing malicious third parties, such as Cambridge Analytica, to access users’ data. In the U.S., these allegations resulted in $5bn in fines from the Federal Trade Commission. In the UK, a similar investigation led by the Information Commissioner’s Office resulted in a fine of £500,000.

This narrow focus of public investigations shows the challenge we face, as a society, in understanding and exposing the true role that online platforms play in political influence. On the one hand, it is unquestionable that Facebook is an enabler of precision-targeted political messages, which requires access to behavioural (observed) data and sophisticated algorithms (both treated by the platform as its “property.”) On the other hand, there is scarce evidence on how intrusive Facebook’s behavioural profiles really are and to what extent users’ vulnerabilities are exploited. From a regulator’s perspective, it is much easier to argue that Facebook’s policy has led to a “security breach” than to prove that microtargeted ads were based on inferred behavioural data and, as such, violated users’ privacy and self-determination.

In this report, we argue that Facebook’s role in microtargeting voters cannot be underestimated. We believe it deserves at least the same attention and scrutiny as the role of so-called malicious third parties, be they data brokers like the infamous Cambridge Analytica or the proverbial Russian spin doctors.

Two pillars of Facebook’s power

Facebook’s ability to influence voters’ behaviour is supported by two pillars:

Data on voters’ behaviour

It has been established by research and journalistic investigations that Facebook constantly monitors users’ behaviour (e.g. their location, social interactions, emotional reactions to content, and clicking and reading patterns). Coupled with algorithmic processing and big data analysis, Facebook is then capable of inferring political opinions, personality traits, and other characteristics, which can be used for political persuasion. As a result, Facebook knows more about citizens than political parties do. Political parties can commission a social survey or even buy customer data (see above), but won’t ever be able to profile the whole population and will never be able to verify these opinions based on facts (actual behaviour). Meanwhile, an estimated 56% of people with voting rights in Poland are Facebook users, and the number is growing. Therefore, it is not surprising that political parties are eager to tap into Facebook’s data to reach potential voters.

Algorithm-assisted ad delivery

Facebook is not merely a passive intermediary between advertisers and users. Rather, the platform plays an active role in targeting ads: Its algorithms interpret criteria selected by advertisers and deliver ads in a way that fulfills advertisers’ objectives. This is especially pertinent in countries where political parties do not have access to voters’ personal data via electoral registries (as is the case in most European countries), or do not engage in sophisticated voter analytics. In such cases, Facebook and other online platforms offer political parties the means to reach specific groups without having to collect data.

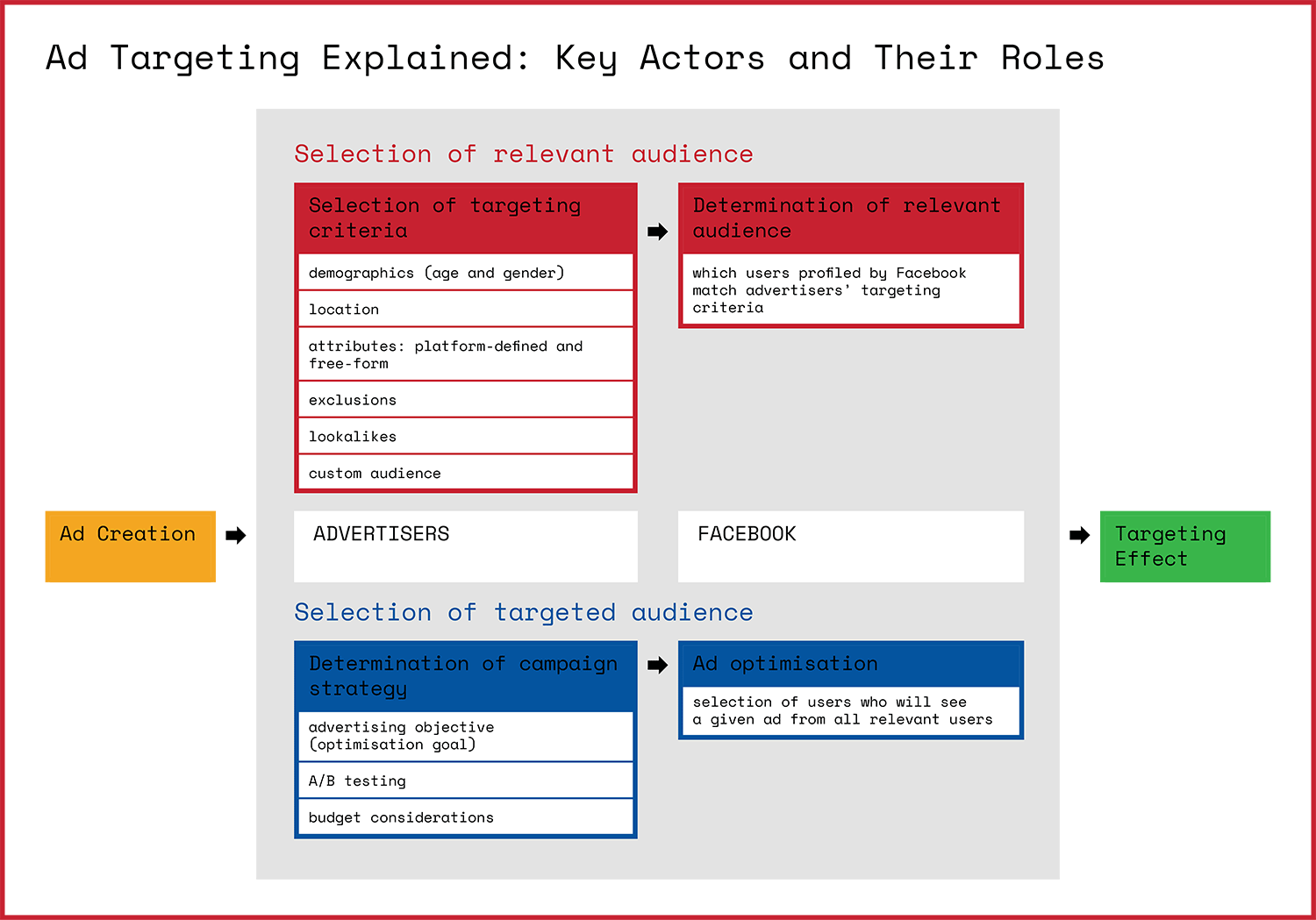

4.Ad targeting explained

In this section, we explain key decisions made in the targeting process. Even though this process is initiated by the advertisers who create ad campaigns and choose the profile of their target audience, the key role still belongs to Facebook. In fact, the platform plays many roles: from data collection and analysis, which enables identifying users’ attributes for advertising purposes, to optimisation of ad delivery, and everything that happens in between. While political advertisers who use Facebook do make their own choices, their choices have been shepherded by Facebook and increasingly rely on data that was collected or inferred by Facebook.

Advertisers’ role: describing their audience

Facebook’s interface for advertisers allows them to select their target audience based on specific characteristics, which are defined by the platform. After making this selection, advertisers can assign their own names to the targeted audience and save for further use. When it comes to defining targeting criteria and campaign strategies, advertisers have the following criteria at their disposal:

- Demographics

Advertisers may select age range and gender, as well as the language spoken by users they wish to target. - Location

Advertisers may select different types of locations: from larger areas, such as country, state, region, city, and election districts (in the U.S.), to very precise areas defined by individual postcodes or a radius as small as one mile from a particular address (e.g. an election rally). For each type of location, advertisers can define whether they want to reach people who live in this location, people who were recently in this location, or people who are travelling in this location. These options make precise geotargeting simple. - Predefined targeting attributes

Facebook allows advertisers to further refine their audience by selecting one or many additional criteria from a list of over 1,000 predefined attributes. These additional options can be based on life events or demographics (e.g. recently engaged users, expectant parents), interests (e.g. users interested in technology or fitness), or behaviours (e.g. users of a particular mobile operating system, people who have travelled recently). - Free-form attributes

In addition to predefined attributes Facebook offers advertisers the possibility to select free-form attributes. In Facebook’s Marketing API, advertisers can freely type user characteristics they are interested in and obtain suggestions from Facebook. Researchers identified more than 250,000 free-text attributes that include Adult Children of Alcoholics, Cancer Awareness, and other sensitive classifications. - Custom audience

Advertisers who have their own sources of data (e.g. customer lists, newsletter subscribers, lists of supporters, or — in some countries — registered voters) can upload them to Facebook. Facebook then matches this uploaded information (e.g. emails) with its own data about users (e.g. emails used for login or phone numbers used for two-factor authentication), without revealing the list of individual profiles to advertisers. This feature enables advertisers to reach specified individuals without knowing their Facebook profile names. - Lookalikes

Advertisers can target users who are similar to an existing audience (e.g. people who liked the advertiser’s Facebook page, or people who visited their website or downloaded their app). In practice, targeting so-called lookalikes entails asking Facebook to find people who are predicted to share characteristics with the seed audience. These lookalikes are determined by Facebook using customer similarity estimations that are constantly being computed by Facebook’s matching algorithm. - Exclusions

Advertisers can also exclude people from their audience, by defining excluded demographics, locations (e.g. an ad should be targeted to users in Poland with the exception of a particular city or region), attributes (e.g. parents excluding those that use the Android operating system), or individual users from the uploaded custom audience list. Regarding the latter: In January 2020, Facebook announced that users will be granted the possibility to opt in to see ads even if an advertiser used a custom audience list to exclude them. - Desired advertising objective and budget considerations

Normally, the size of the relevant audience (users who fit the criteria selected by the advertiser) is bigger than the size of the audience the advertiser can reach with a limited budget. To ensure they reach the most relevant users, advertisers specify their desired advertising objective. This objective is taken into account by Facebook when optimising ad delivery and selecting users for the targeted audience (see more: Facebook’s Role). In the first step of this process, advertisers choose from three broad objectives:- Awareness (aimed at generating interest and usually measured in the number of ad views),

- Consideration (aimed at making people seek more information and usually measured in the number of engagements with content),

- Conversion (aimed at encouraging people to buy or use the product or service advertised and usually measured by analysing specific actions, e.g. store visits, purchases).

Advertisers may also define the timeframe for running the ad, the placement of the ad (e.g. newsfeed, Messenger, right sidebar), and the bid price (e.g. how much they are willing to pay for one ad view). Advertisers can also set limits on their budget (e.g. daily budget caps). - A/B Testing

Advertisers can run A/B tests for particular ad versions, placements, target groups, and delivery-optimisation strategies. Advertisers test ads against each other to learn which strategies give them the best results, and then adjust accordingly.

Facebook’s role: building users’ profiles and targeting ads

Although political parties play an active role in defining their preferred audience, ultimately it is not up to them to decide which users fall into targeted groups. At this stage, key decisions are made by Facebook and are informed by everything Facebook knows about its users (including off-Facebook activity and data inferred by its algorithms). Political advertisers do not have access to the rationale behind these decisions, nor do they have access to the effects of Facebook’s analysis (e.g. individual user profiles). Facebook’s advertising ecosystem is a walled garden controlled and operated by the platform. In fact, as established by other researchers, even if advertisers do not aim to discriminate in how they select their preferred audience, Facebook’s ad delivery and optimisation process can still lead to discrimination and contribute to political polarisation.

Below, we share our insights from investigating how Facebook collects and analyses users’ personal data, builds their profiles, and applies the “magic sauce” that enables effective ad targeting. Please note that we do not have the full picture of that process, because it remains opaque. The understanding that we present below has been based on fragmented information revealed by Facebook (e.g. in its published patents) and on discoveries made by other investigators.

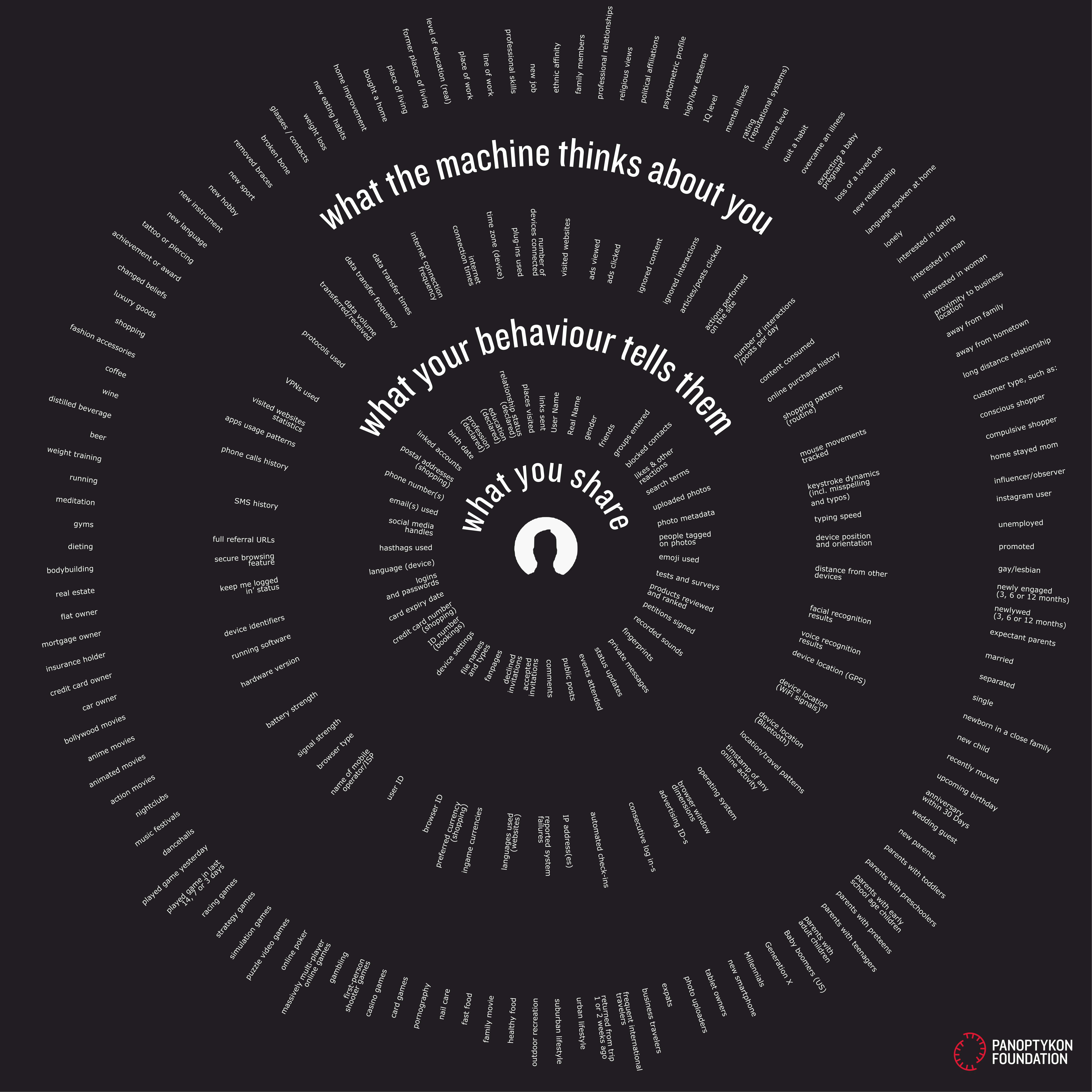

1. Data collection and profiling

Targeting starts with data collection, which provides a foundation for obtaining statistical knowledge about humans and predicting their behaviour. This process is both troubling and fascinating, and there exist many excellent investigations into how Facebook collects and analyses users’ data. (Our favorite is Vladan Joler and SHARE Lab’s series Facebook Algorithmic Factory).

For the purposes of this report, we will only cover the most common sources of data that are relevant to political targeting:

- Data provided by users (e.g. profile information, interactions, content uploaded);

- Observations of user activity and behaviour on and off-Facebook. This ranges from metadata (e.g. time spent on the website), to the device used (e.g. IP addresses), to GPS coordinates, to browsing data collected via Facebook’s cookies and pixels on external websites;

- Data from other Facebook companies, like Instagram, Messenger, Whatsapp, and Facebook Payments;

- Information collected from Facebook partners and data brokers such as Acxiom and Datalogix (discontinued in 2018).

All of this data is analysed by algorithms and compared with data from other users, in the search for meaningful statistical correlations. Facebook’s algorithms can detect simple behavioural patterns (such as users’ daily routines, based on location) and social connections. But thanks to big data analysis, Facebook is also able to infer hidden characteristics that users themselves are not likely to reveal: their real purchasing power, psychometric profiles, IQ, family situation, addictions, illnesses, obsessions, and commitments. According to some researchers, with just 150 likes, Facebook is able to make a more accurate assessment of users’ personality than their parents. A larger goal behind this ongoing algorithmic analysis is to build a detailed and comprehensive profile of every single user; to understand what that person does, what she will do in the near future, and what motivates her.

2. Ad targeting and optimisation

Determination of the relevant audience (ad targeting)

After an advertiser creates an ad campaign and selects criteria for people they wish to reach, it is Facebook’s task to determine which users match this profile. All users who fulfill advertisers’ criteria belong to “relevant audience,” which should not be confused with “targeted audience” (see below).

Depending on how the advertiser selected their target audience, Facebook will have slightly different tasks:

- Demographics, location, or attributes: Facebook will compare advertisers’ criteria with individual user profiles and determine which users meet these requirements;

- Lookalike audience: Facebook identifies common qualities of individuals who belong to the so-called seed audience (e.g. their demographic data or interests). Then, with the use of machine learning models, Facebook identifies users who are predicted to share the same qualities;

- Custom audience list: Facebook matches personal data uploaded by the advertiser with information it has already collected about users (e.g. emails used for login or phone numbers used for two-factor authentication).

Determination of the targeted audience (ad optimisation)

As we mentioned above, an advertiser’s budget usually is not sufficient to reach all Facebook users who match criteria they selected when creating a given campaign (i.e. reach everybody in the “relevant” audience). Therefore, Facebook - with the use of algorithms - makes one more choice: selects users from the relevant audience who should see a given ad (and make it to the “targeted” audience). This is what we call “ad optimisation.” In theory, this process should give the advertisers the best possible result for the money they spend.

In order to select the targeted audience, Facebook take the following factors into consideration:

- Optimisation goal selected by the advertiser (e.g. awareness, consideration, conversion);

- Frequency capping (Facebook will sometimes disregard advertisers who recently showed an ad to a particular user in order not to flood the user with ads from the same advertiser);

- Budget considerations (e.g. daily capping or bid capping);

- Ad relevance score (on the scale from 1 to 10), which is calculated by the analysis of:

- Estimated action rates: predictions on the probability that showing an ad to a person will lead to the outcome desired by the advertiser (e.g. that it will lead to clicks or other engagement);

- Ad quality: a measure of the quality of an ad as determined by many sources, including feedback from people viewing or hiding the ad and assessments of low-quality attributes in the ad (e.g. too much text in the ad's image, withholding information, sensational language, and engagement bait).

Automated Ads: Facebook is in charge of the whole campaign

Facebook offers advertisers a number of features to automate ad creation and targeting, including its Automated Ads service. The idea behind Automated Ads service is simple but powerful: Advertisers can rely on Facebook to prepare an entire advertising campaign, almost from start to finish.

Currently, advertisers can order Facebook to:

- Give them creative suggestions for different versions of ads (e.g. adding call-to-action buttons, text, and other creative details);

- Prepare personalised versions of the ad to everyone who sees it, based on which ad types they are most likely to respond to (so-called dynamic ads);

- Automatically translate ads;

- Suggest automated audiences tailored to an advertiser’s business/activity;

- Recommend budget that will be sufficient for achieving an advertiser’s goals;

- Suggest changes to running ads (e.g. refreshing the image);

- Automate where the ad will appear (automatic ad placement).

These features show that Facebook can play an even more active role in determining which users will be reached with specific ads. The platform can also facilitate microtargeting by creating versions of an ad that will most likely appeal to a particular person. Trends in the marketing industry show that Facebook’s role in ad automation will continue to grow. In the near future, the platform might take over the entire advertising process, from designing the ad creative to determining ad budgets and appropriate groups to target.

Facebook moves towards transparency

Amid scrutiny of how Facebook collects users’ data, builds behavioural profiles, and optimises ad delivery, the platform has taken a few steps toward transparency in recent years. This shift is far from comprehensive, and it likely would not have happened without pressure from European regulators. But it is important to acknowledge.

In September 2018, the European Commission launched the Code of practice against disinformation, a self-regulatory instrument which encourages its signatories to commit to a variety of actions to tackle online disinformation. In terms of advertising, signatories committed to providing transparency into political and issue-based advertising, and to helping consumers understand why they are seeing particular ads. The code has been signed by the leading online platforms including Facebook, Google, and Twitter.

As a signatory, Facebook has committed to offer users the possibility to view more information about Facebook Pages and their active ads; to introduce mandatory policies and processes for advertisers who run political and issue ads; and to give users controls over what ads they see, in addition to explanations of why they are seeing a given ad.

In March 2019, Facebook introduced a public repository of ads in the European Union dubbed the Ad Library (previously functioning in the U.S. under the name of Ad Archive). Simultaneously, Facebook expanded access to the Ad Library application programming interface (API), which allows researchers to perform customised searches and analyse ads stored in the Ad Library.

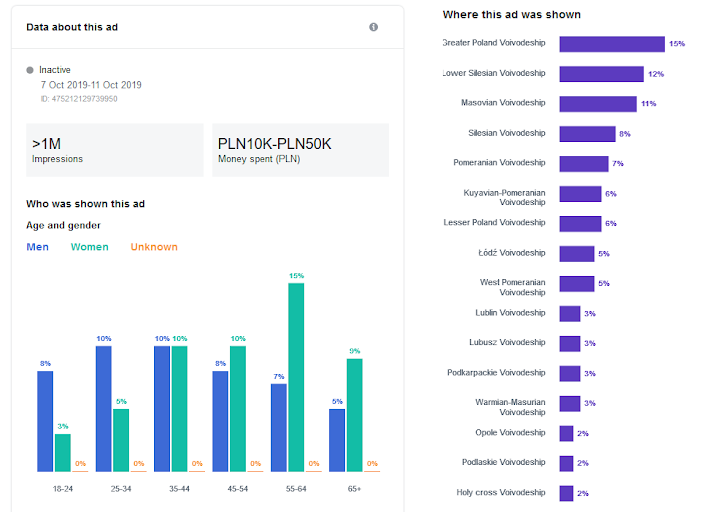

Facebook Ad Library encompasses all advertisements, and additional insights are available for ads related to social issues, elections, or politics. These insights include the range of paid views that the ad received; the range of amount spent on an ad; and the distribution of age, gender, and location (limited to regions) of people who saw the ad. In January 2020, Facebook announced it would add “potential reach” for each political and issue ad, which is an estimated audience size of how many people an advertiser wanted to reach (as opposed to how many they eventually managed to reach). Political and issue ads and insights related to them are archived and remain in the Ad Library for seven years, while other ads are available only during the time they are active.

Advertisers who want to publish political or issue ads are obliged to go through an authorisation process and set a disclaimer indicating the entity that paid for the ad. All Facebook ads are reviewed by a combination of AI and humans before they are shown, in order to verify whether the ad is political, election, or issue related. This review process occurs separately from the self-authorisation of advertisers, which means ads identified as political will appear in the Ad Library anyway, even if the advertiser does not include a disclaimer.

Further, Facebook offers Ad Library reports (also downloadable in CSV format), which include daily aggregated statistics on political and issue ads (e.g. the total spend on ads by country and by advertiser).

In addition to the public repository, Facebook gives users individual explanations about ad targeting. Real-time explanations are accessible by clicking an information button placed next to the advertisement (“Why am I seeing this ad”). Through their privacy settings, users can also access information about their ad preferences; check the list of advertisers who have uploaded their personal data to Facebook; and, as of January 2020, control how data collected about them on external websites or apps is used for advertising (off-Facebook activity). Recently-announced changes will also enable users to opt-out of custom audience targeting, and make themselves eligible to see ads even if an advertiser has used a list to exclude them.

In the second part of this report (see: Facebook transparency and control tools: the crash test), we evaluate these tools.

Part II. Microtargeting in the Polish 2019 election campaign: A case study

Key takeaways

- The scale of microtargeting by Polish political parties was small.

- Nonetheless, our observations suggest that the role of Facebook in optimising ad delivery could have been significant.

- Facebook’s transparency tools are insufficient to verify targeting criteria and determine whether voters’ vulnerabilities were exploited (either by political advertisers or by the platform itself).

- Facebook accurately identifies political ads; only 1% of ads captured by the WhoTargetsMe browser extension and identified as political were not disclosed in the Ad Library.

- The funding entity has not been accurately indicated in 23% of ads published in the Ad Library.

- Political ads in Poland were largely part of an image-building campaign promoting particular candidates. Only 37% of ads were directly related to a political party’s programme or social issues.

- The Polish National Election Commission does not have the tools to effectively monitor and supervise election campaigns on social media, including their financing.

1.Methodology and timeline

Our case study focused on the campaign for the Polish parliamentary elections scheduled for 13 October 2019. In preparation for the main phase, we tested our tools in a pilot run during the European elections in May 2019.

Our research involved:

- Monitoring and analysing political ads on Facebook with the use of data collection and analytics tools;

- Analysing actual campaign expenses and advertising contracts of political parties;

- Analysing observations of other stakeholders, including the National Electoral Commission, the National Broadcasting Council, the Polish Data Protection Authority, OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, and law enforcement agencies.

For the purposes of data collection and analysis, we used the following tools:

- Facebook Ad Library, Ad Library API, and Marketing API;

- AI tools (e.g. natural language processing and computer vision) for data enrichment;

- The WhoTargetsMe browser extension, adapted for the Polish context.

Our analysis of data available in the Ad Library included political ads published by Polish political parties and candidates between 1 August and 13 October 2019, while the WhoTargetsMe extension collected data between 17 August and 13 October 2019. It is important to note that the official election campaign began on 9 August 2019 and finished on 11 October 2019. (On 12 and 13 October, pre-election and election day silence applied.)

The WhoTargetsMe browser extension collects all ads seen by its users, together with individual targeting information available in the “Why am I seeing this ad” feature. The goal of our WhoTargetsMe collaboration was to use crowdsourcing to gather and analyse more insights into ad targeting than those available in the Ad Library. During our case study, over 6,200 Polish Facebook users installed the WTM extension in their browsers. It is important to note that this group was not representative of the entire population, which pushed us to adopt a qualitative rather than quantitative approach to data analysis.

We have also created a searchable database of all political ads collected via the WhoTargetsMe browser extension. The database allows you to filter ads by political party, targeting attribute, and interests. Click to access the tool.

Chart 1. WhoTargetsMe users by gender, age, and political views

2.Polish election context and basic statistics

During the Polish parliamentary elections campaign, we monitored ads published by all election committees registered with the National Electoral Commission. But we focused our detailed analysis on the five committees that registered in all electoral districts:

- Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość);

- Civic Coalition (Koalicja Obywatelska);

- The Left (Lewica);

- Polish People’s Party (Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe);

- Confederation Liberty and Independence (Konfederacja Wolność i Niepodległość).

From a set of over 28,000 political and issue ads available in the Ad Library during the election campaign, we identified 17,673 ads published by political parties and candidates which cost a total of 4,153,850 Polish zlotys (approximately €967,000). For comparison, during the UK general election campaign, which was a month shorter than the Polish one, British political parties published a little over 20,500 ads for nearly £3,500,000 (slightly above €4 million). Facebook’s self-assessment report on the application of the EU Code of practice on disinformation indicates that between March 2019 and 9 September 2019, Poland was eighth highest in the EU27 in terms of the number of political ads, and 13th in terms of money spent on these ads. Taking into consideration the size of the Polish population (over 37 million, fifth in the EU after Brexit), we can say that spending on political ads was very moderate.

The chart below shows how many ads individual political parties published and how much they paid for them. Expenses on Facebook ads (not including the cost of designing ad creatives) constituted a fairly small part of overall campaign budgets. Civic Coalition, the highest spender on Facebook and the biggest opposition committee, spent 8.3% of their campaign budget on Facebook ad targeting. Law and Justice, the winning party, spent 2.6%.

Chart 2. Number of ads and ad spend per committee

We also crowdsourced 90,506 ads via the WhoTargetsMe browser extension, but only 523 of them were political. They were published by eight parties and 126 candidates, with almost half of all political ads sponsored by the Civic Coalition.

Chart 3. Percentage of crowdsourced ads per committee

3.Key findings

I. Microtargeting: not by political parties, but what about by Facebook?

Our analysis shows that despite small amounts spent on ads and relatively small reach (which might suggest that ads were microtargeted), Polish political parties did not use microtargeting techniques at large scale. Candidates targeting ads to particular towns and villages were marginal. Further, the analysis of the content of the ads indicates that Polish political parties largely focused on image-building and did not differentiate messages depending on targeted groups. At the same time, widely-defined audiences paired with small ad budgets might suggest that the role of Facebook in optimising ad delivery (into which we have no insight) was significant (see more: Facebook's Role).

In order to reach these conclusions, we analysed data about ads collected from the Facebook Ad Library and via the WhoTargetsMe browser extension from various perspectives, the most important of which are described in the next sections.

Small ad budgets and ad reach could suggest microtargeting

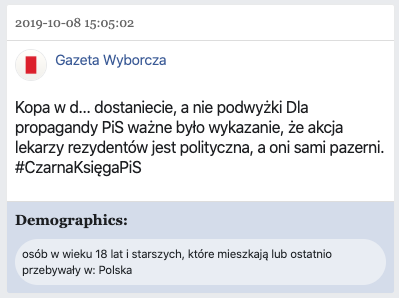

The analysis of amounts spent on political ads revealed that ads with very small budgets of up to 100 Polish zlotys (approximately €25) were dominant for all political parties. For the two leading political parties — Law and Justice and Civic Coalition — they constituted around two-thirds of all purchased ads. The average price of an ad varied between 25 and 340 PLN (€6-79).

Chart 4. Number of ads per ad budget (in PLN)

In terms of reach, most ads were delivered to a maximum of 50,000 people each, with the most popular category being between 1,000 and 4,999 users (the second-smallest reach range presented in the Ad Library). Seven percent of ads reached more than 50,000 users, and only 25 (or 0,1% of all ads) were seen by more than one million people each. Combining data on money spent on ads and ad reach has enabled us to see that in general, a small ad budget translated to small reach. This is intuitive but not to be underestimated, since in the Polish political practice a couple of thousand votes are sometimes sufficient to obtain a seat in the parliament. Only seven ads which cost up to 100 zlotys (€25) reached between 50,000 and 99,000 users. All of these ads were published by the ruling party Law and Justice and were promoting individual candidates and not particular topics on the political agenda. Because of the lack of insight into Facebook’s ad optimisation methods (see more: Facebook's role), we do not know what factors were responsible for these ads standing out.

Chart 5. Comparison of ad reach and ad budget (in PLN)

Small ad budgets and relatively small reach might suggest that particular messages were A/B tested or microtargeted at narrow groups of users. We set out to verify this by analysing individual ad messages, as well as targeted audiences.

No fragmentation in policy messages

We have not identified experiments with various, potentially contradictory messages targeted at different audiences, which are typical for microtargeting. In fact, individual ads often covered multiple topics at once. A vast majority of political ads (65%) was part of an image-building campaign, while ads about direct policy proposals or social issues were less popular. Among them, most often covered topics were: business, environment, women’s issues, transport, health, and education.

Chart 6. Topics of political ads

Negative campaign and hate speech

We have identified a couple campaigns aimed at discouraging potential voters from voting for political opponents. These campaigns were more intense toward the end of the political cycle. Negative ads often focused on building fear around concrete proposals by opponents. Here are some examples:

- Civic Coalition aimed to scare small business owners with the introduction of increased social insurance dues by the ruling Law and Justice;

- The Left criticised Law and Justice’s energy policy based on fossil fuels, and also called for indictment of the justice minister after judiciary reforms;

- Law and Justice prepared videos criticising opponents and sowing fear over their policy proposals or building antipathy for opposition leaders.

It seems these negative ads were targeted at undecided voters. However, because Facebook offers only basic demographic insights into reached groups, it is impossible to determine which characteristics political advertisers targeted (and which characteristics Facebook itself targeted in the process of ad optimisation).

Although the language and messages used in negative ads by Facebook pages of political parties were more sharp, in qualitative analysis we did not identify ads that could be qualified as hate speech or that incited violence against particular groups. At the same time, ads published by individual candidates tended to be more aggressive and included more direct attacks on politicians. The line between an aggressive negative campaign and hate speech is thin and some ads bordered on the latter (if not crossing the line). For instance, the ad on the left side features the motto “Stop the LGBT ideology,” while attacking political opponents (Civic Coalition and The Left) for supporting “modern” Western solutions rather than the traditional Christian family model.

This does not mean the Polish political campaign was free of hate speech. However, hate speech was present in organic, and not sponsored, posts on other social media platforms (e.g. Twitter), or in offline campaigns. What was sponsored on Facebook was often responses to these attacks. For instance, a member of Civic Coalition sponsored an ad with a #StopHate hashtag, in response to an organic Twitter post published by Law and Justice that compared politicians from Civic Coalition to excrement.

Rare examples of precise targeting by political parties

We noted only a few cases of precise targeting of messages to a concrete group of people. Two such cases were the regional campaigns of - respectively - a Civic Coalition and The Left candidates who each created a set of ads (see examples below), with the only difference between messages being the name of the town. This suggests that the candidates made use of Facebook’s precise geotargeting tools.

Straightforward examples like this were rare. Even when looking only at demographics (e.g. gender and age), we noticed that there were very few ads — 1.8% of the total — directly targeted both to a particular gender and to a particular age category. Usually, such ads were targeted to people under the age of 35. In general, political advertisers poorly calibrated their messages to targeted groups and did not specify narrow audiences. For instance, ads about issues relevant to elderly people reached all age groups, but — as a result of Facebook’s optimisation rather than criteria selected by advertisers — were by our estimations more likely to be seen by the elderly. Ads about women’s issues (e.g. feminism, in vitro, contraception, abortion), despite mostly reaching young women, were likely to be seen as often by men and by women over 55. This leads to two conclusions: Political parties did not microtarget ads, and Facebook might have played a significant role in ad optimisation and delivery.

Chart 7. Estimated average number of ad views per topic

Our analysis of Facebook’s explanations to users who saw the 523 political ads collected by the WhoTargetsMe browser extension also confirms these conclusions. Our small sample of ads (please note that it might not be representative of all ads) suggests that political advertisers usually did not use advanced targeting for their ads. Rather, they relied on standard demographic criteria such as age or gender. However, this varied across parties and candidates.

The party that won the elections (Law and Justice) used rather traditional attributes:

- “Demographics” (100% of ads)

- “Speaks language” (86,7% of ads)

- “Interacted with content” (< 1% of ads)

- “Group” (< 1% of ads)

Their main opponent (Civic Coalition) used more advanced features of the Facebook ad engine, such as lookalikes or particular interests:

- “Demographics” (100% of ads)

- “Lookalike” (36,4% of ads)

- “Interests” (33,3% of ads)

- “Likes page” (12,1% of ads)

- “Group” (< 1% of ads)

- “Likes other pages” (< 1% of ads)

In terms of interests selected by advertisers, the three top ones included: “business,” “Law and Justice” (the name of the party), and “European Union.” We have also seen more sensitive criteria such as “LGBT,” “sustainability,” “veganism,” “gender,” and “climate,” but our analysis shows that they were mostly used by The Left (Lewica) and were closely linked to the content of the ad, which simply referred to the party’s programme (e.g. an ad about same-sex marriage was targeted to people interested in “LGBT”). We have not seen these sensitive criteria being used to promote misinformation, polarising content, or messages that were not thematically related to selected interests.

Chart 8. Targeting attributes crowdsourced via WhoTargetsMe and the number of ads

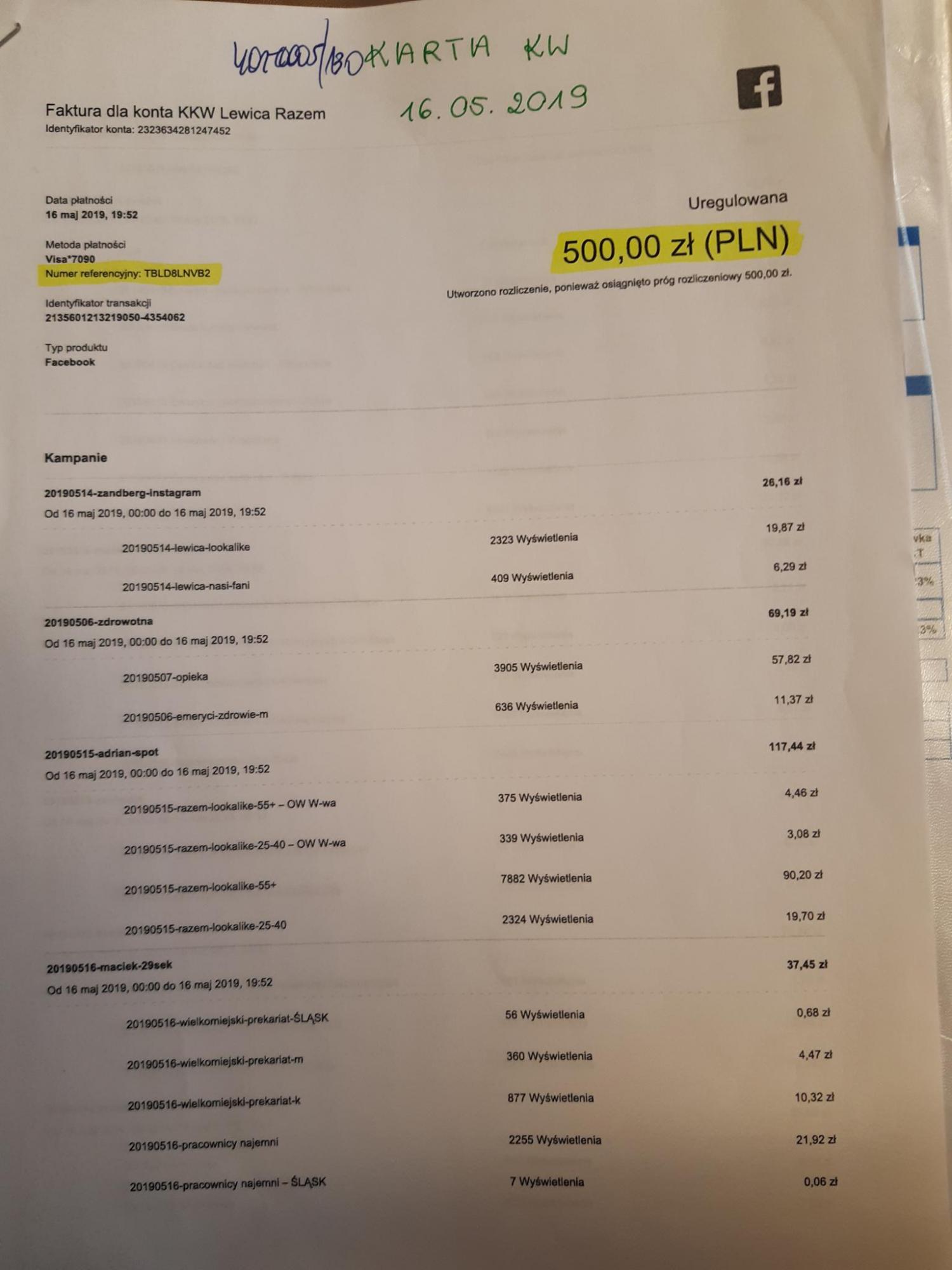

It is important to acknowledge our tools have limitations that prevent us from seeing the full picture of microtargeting. An interesting example of potentially more sensitive and detailed targeting by political advertisers emerged during the analysis of political parties’ financial statements in the National Electoral Commission. The Left (Lewica) submitted an invoice from Facebook which — among other features — disclosed the titles of ad campaigns which included “Fans of Razem [political party],” “Cultural lefties 18-25” (“Lewaki kulturowe 18-25”), and “Tumour - Poland” (“Nowotwór - Polska”). In marketing practices, these titles are often equivalent to the characteristics of targeted groups — and we suspect that it was also the case in this example. This shows that due to the lack of transparency into targeting, we are not getting the full picture of both how political parties choose their audiences and which targeting criteria Facebook chooses to reveal (see: Facebook transparency and control tools: the crash test).

II. Spending on online ads beyond effective control

Financial statements do not offer enough insight

Elections in Poland are regulated by the 2011 Electoral Code and the 1997 Constitution of the Republic of Poland (which introduces the general rule that “the financing of political parties shall be open to public inspection”). Under the Electoral Code, all registered election committees must submit, within three months of the election day, a report on revenues, expenses, and financial obligations to the National Electoral Commission. These provisions are made more specific by a 2011 regulation by the Minister of Finance, which states financial statements should include expenses on external services in connection with “the execution of electoral materials, including conceptual work, design work and production, broken down into (...) online advertising,” as well as with “the use of mass media and poster carriers, broken down by services rendered on (...) advertising on the Internet.” Although the template of the financial statement obliges election committees to present exact amounts spent on online ads, it does not differentiate between social media and online news publishers. As a result, election committees are not obliged to state how much they have spent on ads on online platforms.

An additional hurdle to the analysis of campaign expenses is that all documents are submitted on paper — no electronic version is required (although there are some committees which attach CDs with selected files). Therefore, the actual analysis of financial reports has to be done in person in Warsaw and involves manually browsing thousands of documents.

Invoices submitted to the NEC oftentime present only general information that an intermediary (usually a media agency) received an overall payment for “advertising activities online.” It is impossible to determine how much of it was in fact later transferred to online platforms and for which specific ads.

More detailed invoices that mention payments for “advertising services on Facebook, according to the media plan” lack crucial information (e.g. the said media plan, exact content which was promoted, and what audiences were selected). As the description is quite vague, it is also impossible to determine whether the entire amount was transferred to Facebook or partly to the agency.

The analysis of financial statements after two elections in 2019 shows that most intermediaries are not big agencies or entities specialised in political marketing on social media (in the likes of Cambridge Analytica). Very often, these are small companies dealing with all sorts of marketing (not just political) which provide comprehensive campaign support — not only by running campaigns on Facebook, but also by designing ad creatives and buying advertising space on billboards or broadcast time on local radio.

In addition, the general way of describing the service leaves it open to interpretation. For example, that money was not necessarily used for sponsoring actual ads but for paying influencers or other people to boost organic posts. The latter is not subject to any scrutiny.

As a result, neither researchers nor the oversight body can compare amounts presented in financial statements with financial data published in the Facebook Ad Library.

This may also cause problems in identifying the entity that paid for political ads, as it may not be the election committee directly but rather the employee of the PR firm engaged in the campaign (see remarks about disclaimers below). Documents also lack information about which groups of users were targeted with political ads, when the ad was active, and what was its topic.

The most useful information was available in the detailed invoice issued directly by Facebook to one for the committees which bought ads without help from intermediaries. The invoice contains the titles of campaigns and ads (which can and often do reveal targeted groups; see remarks above), dates the ads ran, the number of views, and the exact amount spent on them. This data enables more scrutiny over party spending on social media. It is also in line with the 2011 Regulation, which obliged committees to submit the actual amount spent online (however, there is no legal requirement to report spending on political ads in social media as a subcategory). When detailed invoices like this are available, the oversight body can compare spending on Facebook with the copy of expense reports from the committee bank account. However, for almost €1 million spent on Facebook ads by all political parties, only The Left presented some invoices issued directly by Facebook.

Facebook does not remove ads without disclaimers fast enough

As mentioned in Part 1 (See: Facebook moves towards transparency), Facebook created an obligation for political advertisers to include a disclaimer indicating the entity that paid for the ad. The Polish Electoral Code also requires all election materials be clearly labeled with the name of the committee. However, despite these requirements, almost one-fourth (23.6%) of all political ads was mislabelled: nearly 1200 political ads ran without any disclaimers at all (7% of all ads), while over 2800 ads (16% of all ads) indicated individuals or media agencies as paying entities. This makes it difficult to verify whether a particular ad was sponsored by a registered election committee and to compare it with financial statements submitted to the National Electoral Commission, which undermines the transparency of campaign spending.

Chart 9. Number of ads and ad spend by funding entity

Looking into the amounts spent on particular types of ads, we have observed that on average less money was spent on ads without disclaimers (on average 84 zlotys as opposed to 288 zlotys for ads paid for by the committee). This means that the reach of ads without disclaimers, and consequently their impact, might not have been as significant. Small amounts spent on ads without disclaimers may also indicate that they were effectively disabled and interrupted by Facebook, as the platform declared before the European elections. However, our analysis of the running time of ads with and without disclaimers shows that this is not really the case.

Chart 10. Average ad running time per funding entity

We have established that ads which ran without a disclaimer were on average emitted longer than ads with disclaimers. Facebook identified and interrupted them with significant delay — on average it took about a week. At the same time, we have observed that most political ads were published in the last days of the election campaign, so fast and effective interruption of ads without disclaimers is key. In our case study, we have seen that the closer it was to the election day, the better job political advertisers did at adding disclaimers. But if this had not been the case, ads without disclaimers would probably have been running until the end of the campaign — which seriously undermines the transparency of political advertising.

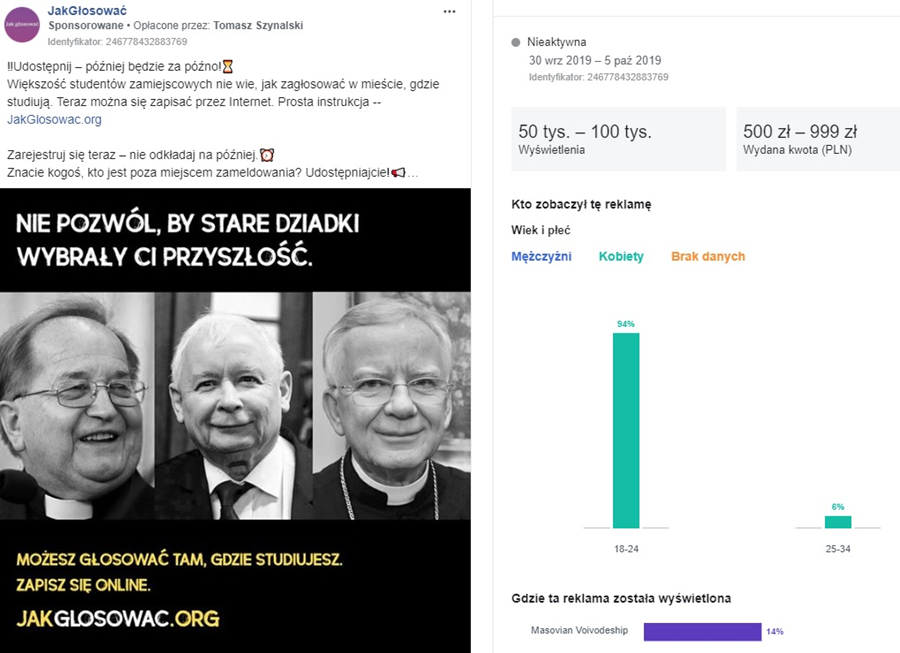

III. Unregulated pro-turnout and media campaigns

In our attempt to identify actors other than political parties or candidates who engaged in sponsoring ads related to elections, we uncovered quite a few ads aimed at encouraging voter turnout and ads from media outlets that had a clear election-related message. Ads in both of these categories were in large part not politically neutral. Indeed, they were quite the opposite — they aimed for selective mobilisation of different groups of voters and included very specific election-related messages.

One example was the “How to vote” campaign targeted mainly to women between 18 and 25 studying and living away from their hometowns. The ads included a link to an instruction on how to register and vote. And the accompanying photo presented faces of Jarosław Kaczyński — the leader of the conservative Law and Justice party — and two famous priests — Tadeusz Rydzyk and archbishop Marek Jędraszewski — along with a slogan: “Do not let old men choose your future.” The ad reached over 50,000 women.

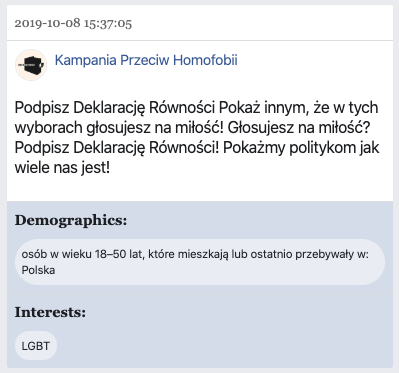

Other pro-turnout campaigns were led by NGOs and also targeted very particular audiences. The example below shows an ad published by Campaign Against Homophobia (Kampania Przeciw Homofobii) — an NGO fighting for LGBT rights — targeting people with the “LGBT” attribute with the pro-turnout slogan “I vote for love.”

A controversial negative campaign against the ruling Law and Justice, which we crowdsourced via the WhoTargetsMe extension, was run by one of the biggest Polish newspapers, Gazeta Wyborcza.

Voter mobilisation ads and political ads from media outlets are beyond the scope of election regulations. At the same time, clear political messages included in these ads rendered these ads relevant in the context of election persuasion.

4.Facebook transparency and control tools: the crash test

Ad Library and Ad Library API

It is beyond doubt that the Facebook Ad Library increased transparency into ads’ content. Researchers and interested users can now see a whole range of ads being promoted, not only those in their personal newsfeeds. However, insights offered for political and issue ads are still insufficient to enable an effective identification of abuses and a thorough analysis of the entire ad targeting process.

While evaluating the Facebook Ad Library, we took three aspects into consideration:

- Comprehensiveness and accuracy

We have established that only 1% of political ads collected via the WhoTargetsMe browser extension were not qualified as political by Facebook and, as a result, were not disclosed in the Ad Library. It is important to note, however, that our sample was relatively small (523 ads). In fact, research from other countries (See: Why we need an ad library for all ads) suggests that the identification of political ads remains a problem. In addition, according to the Polish National Broadcasting Council, there were inconsistencies between the number of ads presented in the Ad Library report — a tool enabling the download of daily aggregated statistics about ads — and the Ad Library itself. These inconsistencies were first observed during the European elections in May and still occurred during the Polish parliamentary elections in October. - Effectiveness of disclaimers

As described in key findings, the funding entity of almost a quarter of all political ads was not correctly disclosed, including 7% that ran without any disclaimer at all. Also, the average running time of ads without a disclaimer was longer than that of ads that were correctly labelled. Facebook was too slow in identifying these cases and in interrupting ads without the indication of the funding entity (this process took about a week). This problem is all the more pertinent given that a vast majority of political ads are published in the last days of the election campaign. - Scope of insights into targeting

The Ad Library does not disclose detailed information on targeting, which makes the social control of political marketing practices impossible. In particular, in the Ad Library we do not see the information about audiences selected by advertisers nor information about optimisation methods used by the platform itself. We only see the outcome of the targeting process (reach) in terms of two basic categories: location (in Poland limited to the region) and basic demographics (gender and age groups) and — since very recently — potential reach. Given that targeting options available for advertisers are way more refined (see: Advertisers' role), our analysis of the Ad Library leads to the conclusion that it is incomplete and presents only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to targeting criteria.

Mozilla on Facebook’s Ad Library API

It is impossible to determine if Facebook’s API is comprehensive, because it requires you to use keywords to search the database. It does not provide you with all ad data and allow you to filter it down using specific criteria or filters, the way nearly all other online databases do. And since you cannot download data in bulk and ads in the API are not given a unique identifier, Facebook makes it impossible to get a complete picture of all of the ads running on their platform

The API provides no information on targeting criteria, so researchers have no way to tell the audience that advertisers are paying to reach. The API also does not provide any engagement data (e.g., clicks, likes, and shares), which means researchers cannot see how users interacted with an ad. Targeting and engagement data is important because it lets researchers see what types of users an advertiser is trying to influence, and whether or not their attempts were successful.

The current API design places major constraints on researchers, rather than allowing them to discover what is really happening on the platform. The limitations in each of these categories, coupled with search rate limits, means it could take researchers months to evaluate ads in a certain region or on a certain topic.

II. Individual ad explanations - Why am I seeing this ad?

Apart from a publicly available repository of ads, Facebook provides users with an individual, personalised explanation of ad targeting via the “Why am I seeing this ad?” feature. Users can access this feature by clicking a button next to ads in their newsfeed. This explanation is available for all ads, not only political and issue ads. It is important to note that Facebook significantly changed the structure, language, and scope of explanations of the feature in the last quarter of 2019, and that our case study covered the period between August and October 2019.

On the basis of our observations and empirical research, we identified the following deficiencies of individual explanations as of October 2019:

- They are incomplete. Facebook reveals only one attribute to users while advertisers can (and usually do) select multiple criteria. Researchers have also established that Facebook does not show whether users were excluded from a particular group, and on the basis of what characteristics. Also, if the advertiser uploads a custom audience list, Facebook does not reveal the type of personal information that was uploaded (e.g. email, phone number).

- They are misleading by:

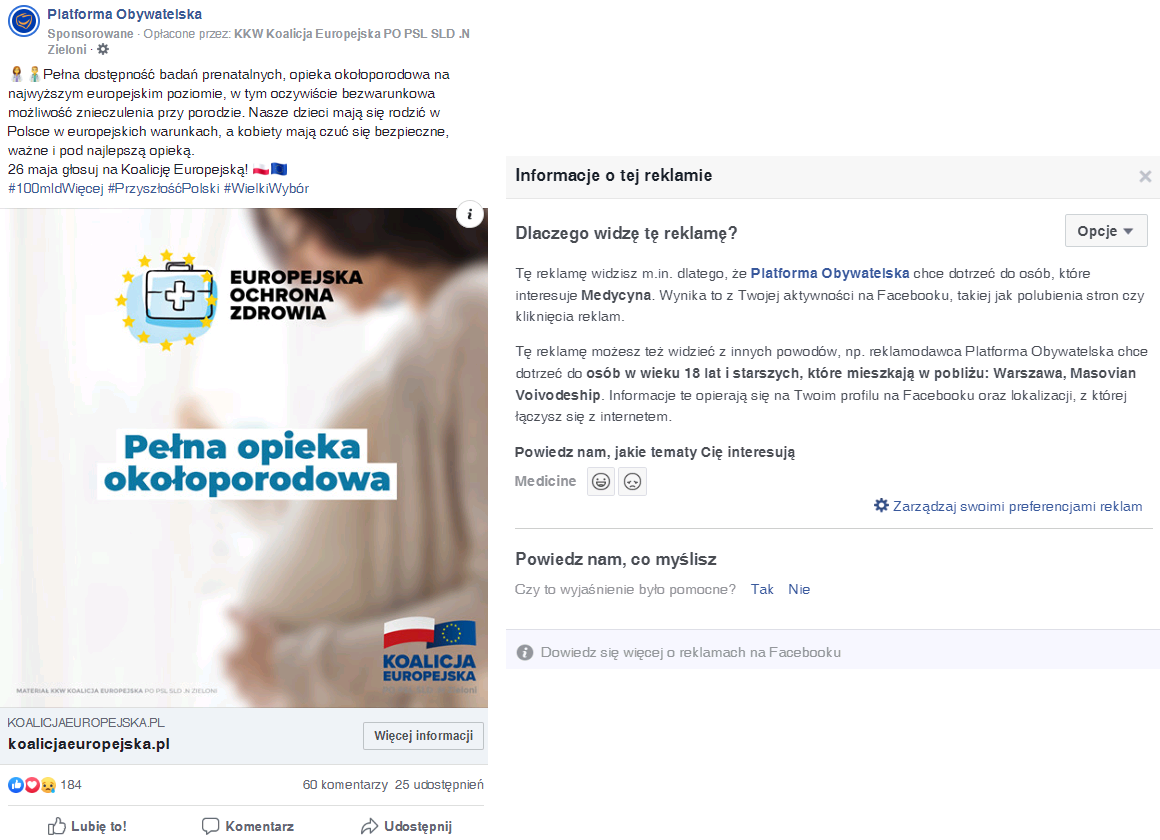

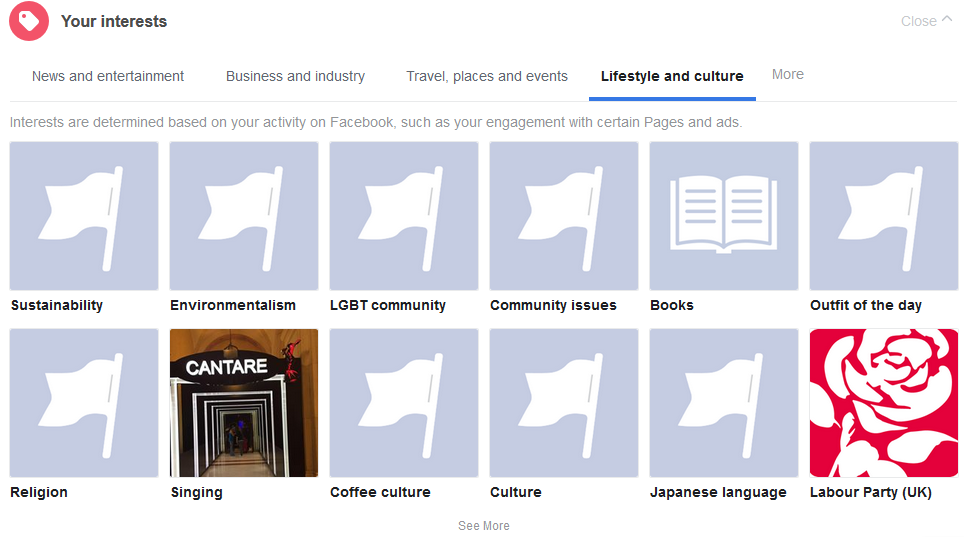

- Presenting only the most common attribute. Facebook shows only the attribute that is linked to the biggest potential audience. For example, if an advertiser selects two attributes — interest in “medicine” (potential reach of 668 million) and interest in “pregnancy” (potential reach of 316 million) — the user’s explanation will only contain “medicine” as the more common attribute. This example is not incidental: During the European elections campaign in May 2019, a person who was pregnant at the time saw a political ad referring to prenatal screenings and perinatal care. “Why am I seeing this ad?” informed her that she was targeted because she was interested in medicine.

- Preferring attributes related to demographics over other types of targeting attributes. Researchers found that whenever the advertiser used one demographic-related attribute (e.g. education level, generation, life events, work, relationships), in addition to other attributes (e.g. recent travel, particular hobbies), the demographic-based attribute would be the one in the explanation.

- Presenting only the most common attribute. Facebook shows only the attribute that is linked to the biggest potential audience. For example, if an advertiser selects two attributes — interest in “medicine” (potential reach of 668 million) and interest in “pregnancy” (potential reach of 316 million) — the user’s explanation will only contain “medicine” as the more common attribute. This example is not incidental: During the European elections campaign in May 2019, a person who was pregnant at the time saw a political ad referring to prenatal screenings and perinatal care. “Why am I seeing this ad?” informed her that she was targeted because she was interested in medicine.

- They do not explain Facebook’s role in ad delivery optimisation. Individual disclosures do not explain why the user was qualified for the targeted audience (e.g. which data provided by the user or which observed behaviour was taken into account). Individual explanations also do not offer any insights into the logic of optimisation.

All of these deficiencies make it impossible for users to fully understand and control how their data is used for advertising purposes.

What has changed after the update?

We are not aware of any studies published after Facebook’s update that address the topic. Our initial insights suggest that the structure and the language of explanations is clearer than before. There is more information available, including the list of criteria selected by advertisers and more than one attribute. But in both cases, without empirical research, it is impossible to say whether this information is comprehensive.

However, with the exception of age determination, users still will not find out which of their characteristics or tracked behaviours were taken into account by Facebook when matching them with a particular ad. For location, interests, and lookalikes, Facebook offers users only a general, non-individualised explanation. This leads us to the conclusion that updated explanations are still incomplete and do not offer meaningful information on why exactly a particular person saw a particular ad.

III. Data transparency and control: settings and ad preferences

Facebook users can gain insight into how their personal data is used for advertising purposes — and, to some extent, control such use of their data — via the Ad Preferences page in their account settings.

In terms of transparency of users’ profiles, we have the following observations:

- Facebook presents the outputs of the profiling process in the form of inferred interests, but it does not offer any meaningful information about the inputs (e.g. what concrete actions and behaviours by the user were responsible for assigning particular interests to them). Instead, Facebook offers generic and vague information (e.g. “you have this preference because of your activity on Facebook related to X, for example liking their Page or one of their Page posts”);

- Facebook presents only interest-based attributes, while hiding other attributes that advertisers can select in the advertising interface (e.g. those related to particular life events, demographics such as income brackets, or inferred education level). The only example of an additional category of attributes that we found is a simple characterisation of Facebook’s users based on their use of internet networks.

- Despite the fact that attributed interests change dynamically (with every advertising campaign), Facebook doesn’t offer users insights into how their profiles change and grow over time;

- Users can see the list of advertisers who uploaded their information to Facebook via the custom audience feature, but Facebook doesn’t reveal what type of information was uploaded (e.g. e-mail, phone number).

In terms of control tools offered by Facebook to its users, we have the following observations:

- Removing individual interests presented in Ad Preferences is not equivalent with removing data that led to this interest being attributed to the user — the only effect is that the user will not see ads based on that interest;

- Facebook’s “Clear history” tool does not allow users to remove data collected by Facebook via pixels and other tracking technologies on other websites and in apps. It only enables removing the connection between this particular source of data and other data Facebook collected about a user;

- Users can only opt out of:

- Ads based on behavioural observations outside Facebook (via Facebook pixels and other trackers), as well as ads based on data about users’ offline activity (e.g. from customer data brokers);

- Seeing ads outside of Facebook (delivered via the Facebook Audience Network);

- Ads about selected topics (political issues are not one of them, but in January 2020 Facebook announced that it will offer users the option to see fewer political ads);

In January 2020, Facebook announced that it will give users more control in relation to how their data is used by advertisers who upload custom audience lists. Users will have the possibility to opt out of seeing ads from a particular advertiser, which were targeted based on the uploaded custom audience list, or make themselves eligible to see ads if an advertiser used a list to exclude them. This suggests that Facebook is not planning to give users the right to globally opt out of all ads targeted with the use of custom audiences.

Facebook’s ad settings have been built on an “opt out” rather than an active “opt in” premise, which means that none of these limitations and restrictions to ad targeting will apply by default. Each and every user has to select them in order to regain some control over the use of their own data for advertising purposes. In Part 3, we argue that this design of advertising settings is not in line with the GDPR standard.

Big unknowns

Because of the opacity of the targeting process and the insufficiencies of Facebook’s transparency tools, it is impossible to comprehensively investigate PMT and the use of users’ data for this particular purpose. From the perspective of both researchers and concerned users, the following gaps are most problematic:

- The Ad Library presents insights limited to platform-defined political and issue ads, which makes it difficult to verify whether election-related content was or was not sponsored by actors other than political parties and candidates;

- These insights are too general and largely insufficient to determine the profile of users who were reached with a specific ad;

- Individual explanations offered to users are incomplete and potentially misleading;

- Users do not have access to their behavioural and inferred data, which often shape their marketing profiles (it is on that basis that Facebook assigns its users particular attributes);

- Control tools offered by Facebook to its users are superficial and do not give them real control over their data and its use for (political) advertising;

- Lack of insight into Facebook’s ad optimisation process (e.g. what prediction models are used) makes it impossible to evaluate its impact and potential risk (in particular, whether ad optimisation may lead to discrimination or enable microtargeting based on sensitive characteristics).

Part III. Recommendations

Country-specific evidence in a pool of other research on the use of PMT

Our case study of how PMT was used in Poland during the 2019 elections added country-specific evidence to a much greater pool of relevant research. From the very beginning of our work, we have been aware of other pending projects and we wanted to use this opportunity to build on each others’ observations. We are confident that by looking at the same problem from the perspective of different countries and by asking slightly different research questions, we are able to bring more value to European discussion on the use (and potential regulation) of PMT.

Being mindful of this common objective, we frequently quote observations made by other researchers who analysed the use of PMT in other countries or looked at advertising practices of online platforms. We invited some of them to comment on our findings and help us develop our final recommendations (see “Expert boxes”). We want to make it very clear that recommendations formulated in this report are based not only on our work in Poland, but also on evidence and arguments published by our peers.

While each of our recommendations can be boiled down to a straightforward demand (in most cases the demand for some form of binding regulation), we see the need to explain the reasoning which has led us to formulate this demand. Therefore each point in this chapter includes background, our argumentation, and dilemmas we faced in the process of developing recommendations.

Below, we place all recommendations on one map in order to show their orientation on two axes: